The hip joint is a ball-and-socket type joint and is formed where the thigh bone (femur) meets the pelvis. The femur has a ball-shaped head on its end that fits into a socket formed in the pelvis, called the acetabulum. Large ligaments, tendons, and muscles around the hip joint hold the bones (ball and socket) in place and keep it from dislocating.

Hip Anatomy, Function and Common Problems

Normally, a smooth cushion of shiny white hyaline (or articular) cartilage about 1/4 inch thick covers the femoral head and the acetabulum. The articular cartilage is kept slick by fluid made in the synovial membrane (joint lining). Synovial fluid and articular cartilage are a very slippery combination—3 times more slippery than skating on ice and 4 to 10 times more slippery than a metal on plastic hip replacement. Synovial fluid is what allows us to flex our joints under great pressure without wear. Since the cartilage is smooth and slippery, the bones move against each other easily and without pain.

When the cartilage is damaged, whether secondary to osteoarthritis (wear-and-tear type arthritis) or trauma, joint motion can become painful and limited.

The hip joint is one of the largest joints in the body and is a major weight-bearing joint. Weight bearing stresses on the hip during walking can be 5 times a person’s body weight. A healthy hip can support your weight and allow you to move without pain. Changes in the hip from disease or injury will significantly affect your gait and place abnormal stress on joints above and below the hip.

It takes great force to seriously damage the hip because of the strong, large muscles of the thighs that support and move the hip.

Anatomical Terms

Anatomical terms allow us to describe the body and body motions more precisely. Instead of your doctor simply saying that “the patient knee hurts”, he or she can say that “the patient’s knee hurts anterolaterally”. Identifying specific areas of pain helps to guide the next steps in treatment or work-up. Below are some anatomic terms doctors use to describe location (applied to the hip):

- Anterior — the abdominal side (front) of the hip

- Posterior — the back side of the hip

- Medial — the side of the hip closest to the spine

- Lateral — the side of the hip farthest from the spine

- Abduction — move away from the body (raising the leg away from midline i.e. towards the side)

- Adduction — move toward the body (lowering the leg toward midline i.e. from the side)

- Proximal — located nearest to the point of attachment or reference, or center of the body

- example: the knee is proximal to the ankle

- Distal — located farthest from the point of attachment or reference, or center of the body

- example: the ankle is distal to the knee

- Inferior — located beneath, under or below; under surface

Anatomy of the Hip

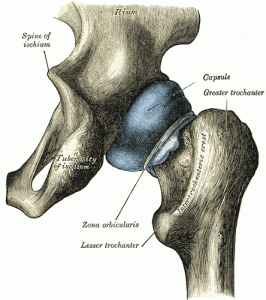

Like the shoulder, the hip is a ball-and-socket joint, but is much more stable. The stability in the hip begins with a deep socket—the acetabulum. Additional stability is provided by the surrounding muscles, hip capsule and associated ligaments. If you think of the hip joint in layers, the deepest layer is bone, then ligaments of the joint capsule, then muscles are on top. Various nerves and blood vessels supply the muscles and bones of the hip.

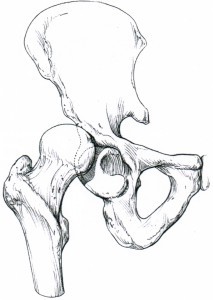

Bony Structures of the Hip

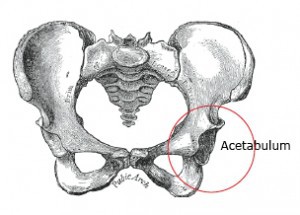

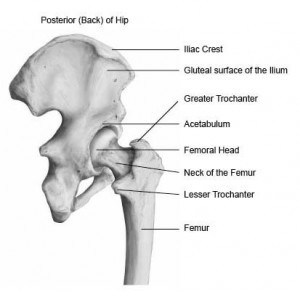

The hip is formed where the thigh bone (femur) meets the three bones that make up the pelvis: the ilium, the pubis (pubic bone) and the ischium. These three bones converge to form the acetabulum, a deep socket on the outer edge of the pelvis. By adulthood, these three bones are completely fused and the pelvis is effectively a single bone.

The femur is the longest bone in the body. The neck of the femur connects the femoral head with the shaft of the femur. The neck ends at the greater and lesser trochanters, which are bony prominences of the femur that various muscles attach to. The greater trochanter serves as the site of attachment for the abductor and external rotator muscles which are important stabilizers of the hip joint. This is the prominent part of your hip that you can actually feel on the outer aspect of your thigh. The lesser trochanter serves as the attachment site of the iliopsoas tendon, one of the muscles that allows you to bend your hip.

It is important to remember that the actual hip joint lies deep in the groin area. This is important, because true hip joint issues are typically associated with groin pain.

The Hip Joint

The hip joint is a ball and socket type joint. The femoral head (ball) fits into the acetabulum (socket) of the pelvis. The large round head of the femur rotates and glides within the acetabulum. The depth of the acetabulum is further increased by a fibrocartilagenous labrum that attaches to the outer rim of the acetabulum. It acts to deepen the socket and to add additional stability to the hip joint. The labrum can become torn and cause symptoms such as pain, weakness, clicking, and instability of the hip.

There are numerous structures that contribute stability to the hip:

- The ball and socket bony structure

- The labrum

- The capsule and its associated ligaments: e.g. iliofemoral ligament, pubofemoral ligament

- The surrounding muscles including the abductors (gluteus medius and minimus) and external rotators (gemelli muscles, piriformis, the obturators).

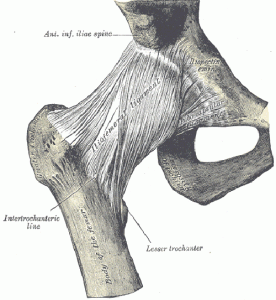

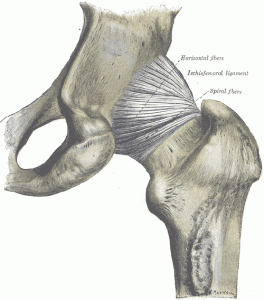

Hip Ligaments

The stability of the hip is increased by the strong ligaments that encircle the hip (the iliofemoral, pubofemoral, and ischiofemoral ligaments). These ligaments completely encompass the hip joint and form the joint capsule. The iliofemoral ligament is considered by most experts to be the strongest ligament in the body. The ligamentum teres is a small tubular structure that connects the head of the femur to the acetabulum. It contains the artery of the ligamentum teres. In infants, this serves as a relatively important source of blood supply to the head of the femur. In adults, the ligamentum teres is thought by most to be more of a vestigial structure that serves little function.

Muscles of the Hip

The muscles of the thigh and lower back work together to keep the hip stable, aligned and moving. It is the muscles of the hip that allow the movements of the hip:

- flexion – bend

- extension – straighten

- abduction – leg move away from midline

- adduction – leg moves back towards midline

- external rotation (allows for the foot to point outwards)

- internal rotation (allows for the foot to point inward)

The hip muscles are divided up into three basic groups based on their location: anterior muscles (front), posterior (back), and medial (inside). The muscles of the anterior thigh consist of the quadriceps (or quads): vastus medialis, intermedius, lateralis and rectus femoris muscles. The quads make up about 70% of the thigh’s muscle mass. The main functions of the quads are flexion (bending) of the hip and extension (straightening) of the knee.

The gluteal and hamstring muscles, as well as the external rotators of the hip are located in the buttocks and posterior thigh. The gluteal muscles consist of the gluteus maximum, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus. The gluteus maximus is the main hip extensor and helps keep up the normal tone of the fascia lata or iliotibial (IT) band, which is the long, sheet-like tendon on the side of your thigh. It helps with motion of the hip, but perhaps more importantly, acts to help stabilize the knee joint.

Gluteus medius and minimus are the main abductors of the hip —that is, they move the leg away from the midline of the body (using the spine as a midline reference point). They also are the main internal rotators of the hip (i.e. turn the foot inwards). The gluteus medius and minimus are also important stabilizers of the hip joint and help to keep the pelvis level as we walk.

The tensor fascia lata (TFL) is another abductor of the hip, which, along with the gluteus maximus, attaches to the IT band. The IT band is a common cause of lateral (outside) hip, thigh, and knee pain.

The medial muscles of the hip are involved in the adduction of the leg i.e. bringing the leg back towards the midline. These muscles include the adductors (adductor magnus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, pectineus, gracilis). Obturator externus also helps to adduct the leg.

The external rotator muscles (piriformis, gemelli, obturator internus) of the hip are located in the buttock area and assist in lateral rotation of the hip (out-toeing). Lateral rotation is needed for crossing the legs.

Blood Vessels and Nerves of the Hip

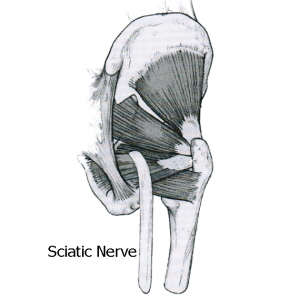

Nerves carry signals from the brain to the muscles to move the hip and carry signals from the muscles back to the brain about pain, pressure and temperature. The main nerves of the hip that supply the muscles in the hip include the femoral, obturator, and sciatic nerves.

The sciatic nerve is the most commonly recognized nerve in the hip and thigh. The sciatic nerve is large—as big around as your thumb—and travels beneath the gluteus maximus down the back of the thigh where it branches to supply the muscles of the leg and foot. Hip dislocations can cause injury to the sciatic nerve.

The blood supply to the hip is extensive and comes from branches of the internal and external iliac arteries: the femoral, obturator, superior and inferior gluteal arteries. The femoral artery is well-known because of its use in cardiac catheterization. You can feel its pulse in your groin area. It travels from deep within the hip down the thigh and down to the knee. It is the continuation of the external iliac artery which lies within the pelvis. The main blood supply to the femoral head comes from vessels that branch off of the femoral artery: the lateral and medial femoral circumflex arteries. Disruption of these arteries can lead to osteonecrosis (bone death) of the femoral head. These arteries can become disrupted with hip fractures and hip dislocations.

Bursae

Bursae are fluid filled sacs lined with a synovial membrane which produce synovial fluid. Bursae are often found near joints. Their function is to lessen the friction between tendon and bone, ligament and bone, tendons and ligaments, and between muscles. There are as many as 20 bursae around the hip. Inflammation or infection of the bursa called bursitis.

The trochanteric bursa is located between the greater trochanter (the bony prominence on the femur) and the muscles and tendons that cross over the greater trochanter. This bursa can get irritated if the IT band is too tight. This bursa is a common cause of lateral thigh (hip) pain. Two other bursa that can get inflamed are the iliopsoas bursa, located under the iliopsoas muscle and the bursa located over the ischial tuberosity (the bone you sit on).

Common Problems of the Hip

- Osteoarthritis

- Dislocation (see image above of simple dislocation)

- Bursitis

- Fracture

- Femoroacetabular impingement

- Labral tear

- IT band syndrome

- Snapping hip syndrome

- Aseptic or Avascular necrosis

- Congenital Dislocation

- Acetabular dysplasia

- Coxa valga

- Coxa vara

- Tumor

- Legg-Perthes disease

Surgery of the Hip

- Hip Replacement

- Hip arthroscopy

- Hip fracture fixation

- Hip preservation surgery

The hip joint is largely responsible for mobility. So any injury, trauma, or disease that affects its function can significantly reduce a person’s independence.

Lastly, there are many conditions in and around the hip and even conditions of the spine, that can cause pain in the hip area. Therefore, if you suspect that you might be having a problem with your hip(s), don’t hesitate to visit a trusted doctor for further evaluation.

Note that the information in this article is purely informative and should never be used in place of the advice of professionals.