Diagnosis, Treatment, and Surgery for Shoulder Problems

- Shoulder Arthroscopy

- Shoulder Replacement

- Shoulder Rehab and Shoulder Replacement Recovery Time

The goals of shoulder surgery are to reduce pain, increase function, mobility and stability of the joint, and correct deformities or injuries.

The shoulder has a wider and more varied range of motion than any other joint in the body. Our shoulder allows us to do everything from paint to play basketball, but this flexibility also makes the shoulder joint more prone to injury.

Those most at risk for shoulder problems are athletes or workers with “overhead” movements—swimmers, throwers, painters and construction workers. The older we get, the more vulnerable to injury we all are.

The shoulder is not a single joint, but a complex arrangement of bones, ligaments, muscles, and tendons that is better called the shoulder girdle. The primary function of the shoulder girdle is to give strength and range of motion to the arm. The shoulder girdle includes three bones—the scapula, clavicle and humerus.

Anatomical Terms

Anatomy terms allow us to describe the body and body motions more precisely. Instead of your doctor simply saying that “the patient knee hurts”, he or she can say that “the patient’s knee hurts anterolaterally”. This is useful information, as the specific location of pain around body structures helps doctors and other health care providers to figure out what the cause of the patient’s pain is. The next steps in treatment or work-up can then be started. Below are some anatomic terms doctors use to describe location (as applied to the shoulder):

- Anterior — the front of the shoulder

- Posterior — the back of the shoulder

- Medial — the side of the shoulder closest to mid body

- Lateral — the side of the shoulder farthest from mid body

- Proximal — located nearest to the point of attachment or reference, or center of the body

- example: the elbow is proximal to the wrist

- Distal — located farthest from the point of attachment or reference, or center of the body

- example: the wrist is distal to the elbow

- Inferior — located beneath, under or below; under-surface

The following are some basic terms used to describe shoulder motion:

- Abduction — movement away from the body (raising the arm to the side)

- Adduction — movement towards the body (lowering the arm)

- Internal rotation – with elbow at 90 degrees and pressed against side (hand straight out in front), shoulder rotates inward so hand moves towards belly

- External rotation – with elbow at 90 degrees and pressed against side (hand straight out in front), shoulder rotates outwards so hand moves away from belly

Shoulder Anatomy

To keep things simple, we can divide the shoulder into layers. Starting with what is deepest, it goes: bone, then ligaments of the joint capsule, with tendons and muscles on top. There are many nerves and blood vessels that supply the muscles and bones of the shoulder. Nerves are like electrical wires that carry signals from the brain to the muscles to allow for movement of the shoulder. They also carry signals from the shoulder back to the brain about pain, pressure and temperature.

Bones of the Shoulder Girdle

The bones of the shoulder girdle include the scapula, the humerus, and the clavicle.

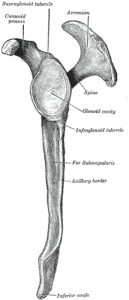

Scapula (shoulder blade)

The scapula is the most complex of the shoulder bones. It floats on the rib cage and is attached to it only by muscles. There are three important landmarks on the scapula: the spine of the scapula, the acromion, and the coracoid process. The spine of the scapula (not to be confused with the actual spine that helps us stand upright) divides the back of the scapula into two sections. The supraspinatus is one of the rotator cuff muscles (described later), that sits above the spine. The infraspinatus is one of the muscles that sits below the spine. The acromion forms the roof of the glenohumeral joint and meets with the clavicle to form the acromioclavicular (AC) joint. The coracoid process serves as an important attachment point for many muscles and ligaments.

Humerus (upper arm). The humerus is the upper arm bone. It is divided into the head, anatomic neck, surgical neck, and shaft. The head of the humerus forms the ball portion of the ball-and-socket like glenohumeral joint. Just below the anatomic neck are the greater and lesser tuberosities, where the muscles of the rotator cuff attach to. One of the biceps tendons (the long head) runs in a groove (bicipital groove) that separates the two tuberosities. Just below the tuberosities is the surgical neck of the humerus and is the most common area for fractures (breaks) of the proximal humerus.

Clavicle (collar bone)

The clavicle connects the sternum (breastbone) to the scapula via the acromion. The clavicle helps hold the shoulder out to the side while allowing the scapula to still move around. Importantly, it is held in place by multiple ligaments including the sternoclavicular ligament (at the sterno-clavicular joint), acromioclavicular ligament (at the acromioclavicular joint), and coracoclavicular ligaments. Injury can occur to any of these ligaments. Fractures (breaks) of the clavicle can also occur and are not uncommon.

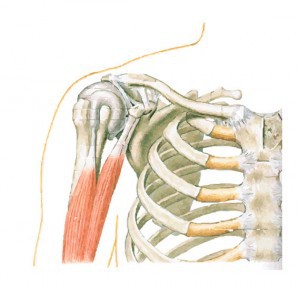

Shoulder Muscles and Shoulder Tendons

Muscles allow us to move by pulling on bones. Tendons are pulley-like connective tissue structures that attach muscles to bone.

Around the shoulder, muscles in the back, neck, shoulder, chest and upper arm all work together to support and move the shoulder. Each muscle of the shoulder assists with specific movements. One of the most important of these for shoulder motion is the deltoid. It is one of the main muscles that allows us to bring our arm out in front of us, to the side, and behind us.

The Biceps

The biceps actually has two (i.e. biceps) heads and thus two attachments around the shoulder. The short head of the biceps comes from the coracoid process. The long-head of the biceps tendon runs in the groove between the two tuberosities of the humerus on the front of the shoulder and attaches to the upper end of the glenoid labrum inside the glenohumeral joint (see joint anatomy below). The biceps attaches to the radius bone in the forearm and allows us to bend our elbow and bring our hand from a palm-down position to a palm-up position (supination).

The long head of the biceps can be a significant source of pain and is sometimes surgically released for this reason.

The Rotator Cuff

The rotator cuff consists of four muscles and their associated tendons (pulleys) that originate on the scapula and attach to the tuberosities of the humerus. By wrapping mainly around the top of the head of the humerus (ball), the main function of the rotator cuff is to keep it centered in the glenoid (cup) as the shoulder moves. They also help to lift and rotate the shoulder in the many directions.

The rotator cuff muscles include (the):

- Supraspinatus

- Infraspinatus

- Teres minor

- Subscapularis

Overuse and traumatic injuries to the rotator cuff are two of the more common problems of the shoulder. Additionally, the rotator cuff muscles are the muscles most often targeted in shoulder rehab.

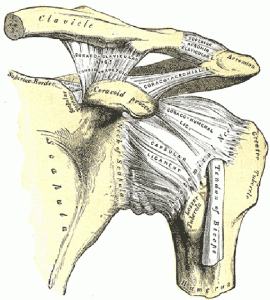

Shoulder Ligaments

Ligaments are sturdy, band-like structures that connect bones to other bones and are important for stability. Once stretched, they tend to stay stretched and if stretched too far, they can tear.

There are several important ligaments about the shoulder girdle. Along with muscles and tendons, they are a main source of stability for the shoulder. Shoulder ligaments also form the joint capsule that surround the glenohumeral joint.

These are the main ligaments that help to stabilize the joints of the shoulder:

- Acromioclavicular ligaments (several) and coracoclavicular ligaments (there are two: trapezoid and conoid). These ligaments stabilize the acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

- Sternoclavicular ligaments (many) stabilize the sternoclavicular (SC) joint.

- There are many glenohumeral ligaments that help to stabilize the glenohumeral (GH) joint.

Injury to the acromioclavicular ligament and/or the coracoclavicular ligaments may be as simple as an AC joint sprain to a separated shoulder. Injuries to the glenohumeral ligaments can occur with shoulder dislocation. Injuries to the sternoclavicular ligaments are much less common.

The Shoulder Joints

A joint is formed where two or more bones meet. Motion usually occurs around joints. There are three true joints in the shoulder girdle. Of these, the glenohumeral joint is the most important for shoulder motion. It is this joint that most people commonly think of as the shoulder joint.

- The glenohumeral joint (GH) – a ball-and-socket type joint where the head of the humerus (ball) meets the glenoid (socket) on the scapula.

- The acromioclavicular joint (AC) – a gliding type joint where the acromion on the scapula links to the clavicle (collar bone). Not much motion occurs here.

- The sternoclavicular joint (SC) – a gliding type joint between the sternum (breastbone) and the clavicle (collar bone). Again, not much motion occurs here.

- There is actually a fourth “joint” called the scapulothoracic “joint”. It is where the scapula meets the back of the rib cage. About a 1/3 of shoulder motion does occur here.

The stability of the GH joint depends on keeping the humeral head (ball) centered within the glenoid (socket) on the scapula. The humerus is held in place with ligaments, tendons and muscles. These important tendons and muscles include the rotator cuff muscles, biceps tendon, and the deltoid muscle discussed above.

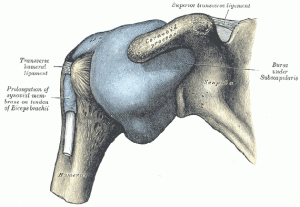

The Glenohumeral Joint (GH)

While the GH joint is indeed a ball-and-socket joint much like the hip joint, it differs in that it is not a weight bearing-joint like the hip. Furthermore, the hip joint has a ball that sits in a very deep socket. This makes the hip joint very stable. On the other hand, the ball of the shoulder (the head of the humerus) only loosely fits in a shallow cup (the glenoid). It is very much like a golfball on a tee. As a result of this unique structure, the GH joint has the greatest mobility of any joint in the body, with free movement in almost any direction. Unfortunately, however, these qualities also make the shoulder less stable than the hip and more prone to injury.

There are important soft tissue structures that also help to stabilize the GH joint. The most important of these are:

- The joint capsule and glenohumeral ligaments – help to stabilize the GH joint

- The glenoid labrum – this is a ring shaped structure that is attached to and wraps around the rim of the glenoid; it increases the depth of the glenoid “socket” by 50%. It helps to create a better fit for the head of the humerus (ball) in the glenoid (socket) and helps to stabilize the joint. The shoulder capsule, glenohumeral ligaments, and the long head of the biceps tendon also attach to it.

- The long head of the biceps tendon

- The rotator cuff

- The deltoid muscle

Again, these soft tissues are where most degenerative (wear and tear) conditions and traumatic injuries of the shoulder occur.

Cartilage in the Shoulder Joint

There are many types of cartilage in our body, each with a slightly different function. For instance, the glenoid labrum (discussed above) is made up of fibrocartilage which makes it strong and rubbery and able to perform its function of improving shoulder stability. On the other hand, like bones of most joints, the head of the humerus (ball) and glenoid (socket) are covered in hyaline cartilage. Hyaline (also known as articular) cartilage is both flexible and slippery. The flexibility helps it to act as a shock absorber. Articular cartilage is made even more slippery by an oily lubricant made within the joint, called synovial fluid. This slickness allows for smooth motion between the two bones of the GH joint — allowing them to move against each other easily and without pain. However, if this articular cartilage wears away and the underlying bone becomes exposed, joint movement can become painful (this is known as arthritis).

Hyaluronic acid injections are sometimes used to treat arthritis. They are mean to mimic the natural synovial fluid described above (i.e. joint lubricant)

Shoulder Bursae

Bursae are everywhere in the body. A bursa is simply a slippery, padlike sac found between two moving surfaces that reduces friction and aids in movement. They are often found between tendon and bone, ligament and bone, tendons and ligaments, and between muscles. Sandwiched between the rotator cuff muscle and the outer layer of large bulky muscles in the subacromial space (see below) is the large subacromial bursa, called the subdeltoid bursa.

Bursa can oftentimes become irritated and inflamed. Inflammation of the bursa can cause pain. This is why anti-inflammatory medication and steroid injections (a more powerful anti-inflammatory) can offer pain relief.

The Subacromial Space

The space between the acromion and rotator cuff below is called the subacromial space. The subacromial bursa is sandwiched into this space. Bone spurs of the acromion can narrow this space and irritate the bursa causing pain.

These bone spurs are sometimes shaved down during surgery (known as an acromioplasty).

Blood Vessels and Nerves in the Shoulder

There are many important nerves that exist around or pass by the shoulder. Shoulder dislocations and surgical neck fractures (breaks) of the humerus can therefore be accompanied by nerve injury. Nerve injury can cause weakness and or loss of feeling around the shoulder.

The blood supply to the shoulder is very abundant, for the most part.

Problems of the Shoulder

- Acromioclavicular ligament injuries (sprains)

- Adhesive capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder)

- Acromioclavicular joint arthritis

- Glenohumeral joint arthritis – Osteoarthritis, inflammatory (Rheumatoid)

- Cuff tear arthropathy

- Little leaguer’s shoulder

- Calcific Tendonitis

- Fractures

- Impingement Syndrome (Bursitis)

- Labral tear – anterior, posterior

- Biceps tendonitis

- Osteonecrosis (bone death)

- Rotator cuff syndrome

- Shoulder instability (dislocation)