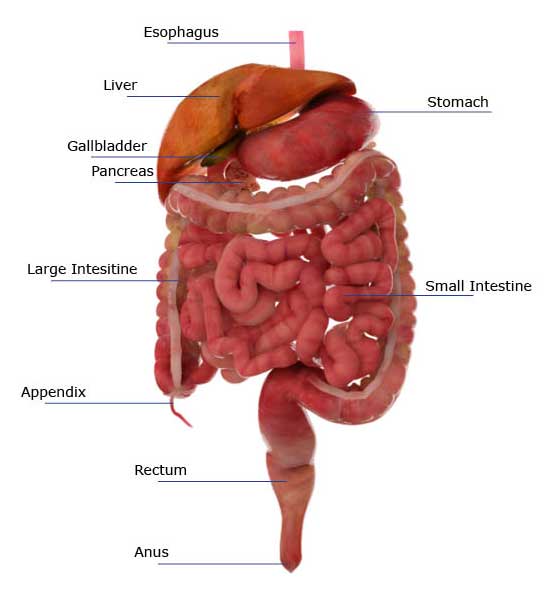

The digestive system is essential for the health of the human body. It breaks down the foods we eat into smaller components that can be absorbed by the cells of the body for energy. This process is known as digestion. It involves chewing food, moving it through the digestive tract, breaking down large particles into molecules, absorption of nutrients into the bloodstream, and removing residual waste from the body.

This system is composed of a group of organs, each of which has its own job in the digestive process. The digestive tract itself is one long tube that begins at the mouth, and ends at the anus. In a fully grown adult, it is approximately 30 feet (9 meters) long.

The digestive system includes the esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines, along with accessory organs such as the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and salivary glands. These organs produce enzymes and chemicals that help digest food. It takes several days for food to pass from the mouth to the end of the digestive tract.

Digestion occurs in 2 ways: mechanical and chemical. Mechanical digestion first occurs in the mouth. The teeth break food into smaller pieces. Once in the stomach, food is churned and broken down into even smaller pieces. The chemical digestion happens throughout the digestive tract via saliva, stomach acid, enzymes, and other chemicals that further dissolve and process the food, releasing important nutrients. Such nutrients include fats, carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, and minerals.

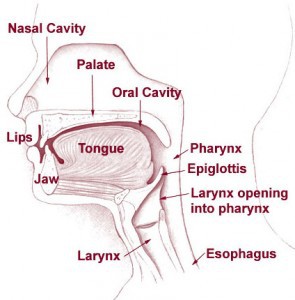

Mouth

The process of digestion begins inside the mouth, where the first and second molars chew (masticate) food to break it down into smaller pieces. Food is also exposed to salivary enzymes. Saliva is secreted by glands located under the tongue, within the cheeks, and near the lower jaw.

The process of digestion begins inside the mouth, where the first and second molars chew (masticate) food to break it down into smaller pieces. Food is also exposed to salivary enzymes. Saliva is secreted by glands located under the tongue, within the cheeks, and near the lower jaw.

Saliva softens the food, and allows it to become a soft mass that can be easily swallowed. It also contains amylase and other enzymes that start the digestive process by breaking down complex carbohydrates into simple sugars. The digestion of proteins does not occur in the mouth.

The tongue then pushes the softened mass of food, called a bolus, toward the back of the mouth. This food bolus is swallowed, then transported via the muscle contractions of the esophagus into the stomach. The soft palate, portion of the mouth, near the throat, presses upward prevent food from going up into the nasal cavity. The epiglottis, a flap-like covering over the trachea (windpipe), reflexively closes when the food bolus enters the esophagus to prevent aspiration.

Esophagus

The food bolus enters a long muscular tube called the esophagus. This portion of the digestive tract is about 10 inches long, and connects the throat to the stomach. Food moves through the esophagus using a series of muscle contractions known as peristalsis. Muscles within the lining of the esophagus contract in a wavelike pattern to propel food downward.

A ring-like muscle, called the lower esophageal sphincter, sits at the point where the esophagus meets the stomach. It is also know as the “cardiac” sphincter due to its proximity to the heart. This muscle relaxes to allow the passage of food into the stomach, then tightens to prevent it from returning into the esophagus.

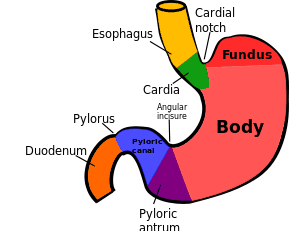

Stomach

Between the esophagus and small intestine lies a pear-shaped, muscular “sac” called the stomach. This organ is approximately 12 inches long, and 6 inches at its widest section. However, because of the muscular wall elasticity, the size and shape of the stomach can change depending on the amount of food within it.

Between the esophagus and small intestine lies a pear-shaped, muscular “sac” called the stomach. This organ is approximately 12 inches long, and 6 inches at its widest section. However, because of the muscular wall elasticity, the size and shape of the stomach can change depending on the amount of food within it.

The stomach consists of five layers. The innermost mucosal layer is protected by mucus to prevent irritation from the stomach’s contents. The gastric mucosa also has many folds on its surface, called rugae, which expand when food is present. Gastric juice is produced within this lining which consists of hydrochloric acid, lipase, and pepsin. The middle stomach layer, or submucosa, contains the muscles that contract to grind and mix food. The outermost stomach layer is divided into the subserosa and serosa.

Fat and protein digestion occur in the stomach. These nutrients are broken down into their basic components, amino acids and fatty acids. Only a small amount of carbohydrate digestion occurs here because the stomach acids are too strong. However, substances like water and alcohol are absorbed directly from the stomach into the bloodstream. Food undergoes digestion in the stomach for up to five hours.

As food is churned with gastric juice, it is converted into a semifluid mixture, called chyme. This very acidic food mixture then passes into the small intestine. Once it enters small intestine, carbohydrate digestion resumes. The small intestine is also where your body begins to absorb the nutrients from food.

To enter the small intestine, chyme must pass through the pyloric sphincter. This thick, ring-like muscle separates the stomach from the initial portion of the small intestine, or duodenum. It typically remains closed, but relaxes and opens to allow the acidic chyme to enter the small intestine, and prevent back flow.

Small Intestine

The small intestine is divided into three parts—the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. It is approximately 20 feet long and 1 inch in diameter. If you place a flattened palm on your belly button, your hand covers most of the area where the small intestine is coiled. This portion of the digestive tract is lined with a protective mucus to prevent irritation from acid and digestive enzymes. Beneath this mucous layer are thousands of tiny folds and projections called villi. Each villus has even smaller microvilli which are important for nutrient and electrolyte absorption. They are more numerous in the initial 2/3 of the small intestines.

The most important aspect of small intestine is that it absorbs what the body needs. This includes 90% of all proteins, fats, and carbohydrates consumed. These nutrients enter the bloodstream in the form of amino acids, simple sugars, vitamins, and minerals. Fatty acids, cholesterol, and vitamins A, D, E, and K first enter via the lymphatic system, and then travel to liver via the bloodstream. In the liver, they are processed, then are sent out to other cells in the body.

Duodenum

This is a 10-inch long C-shaped tube that circles the head of the pancreas. It is the first part of the small intestine that accepts the chyme from the stomach. Here, the acidic chyme is neutralized by bile and other enzymes. Bile is produced by the liver, stored in the gall bladder, and secreted into the duodenum. Pancreatic enzymes are also released into this part of the small intestine. Absorption of vitamins, minerals and other nutrients begin here. In particular, the majority of iron, calcium, and magnesium are absorbed. The remaining food continues on to the jejunum.

Jejunum

The second (middle) section of the small intestine is a coiled tube which is thicker and more vascular than the ileum. It lies near the belly button area of the abdomen. Like the duodenum, the mucosal walls of the jejunum are also lined with villi and microvilli. Their function is to increase the surface area for better absorption of nutrients. This is important because the majority of absorption occurs in this part of the digestive tract. Simple sugars, some B vitamins, and amino acids pass from the villi directly into the blood stream. Fats travel via the lymphatic capillaries. Any remaining food then passes into the ileum.

Ileum

The last part of the small intestine is located in the pelvis. There is no specific demarcation that separates the jejunum and ileum. However, this section of the intestines differs in that its walls are thinner, and it has fewer blood vessels.

This is where the final absorption of nutrients occurs: amino acids, fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K), fatty acids, cholesterol, and B12. Some amount of sodium and potassium absorption occurs here as well. Vitamin B12 absorption is very important to prevent deficiencies that can cause abnormal red blood cells and neurological problems. Past this section of the small intestine, any unabsorbed or undigested food enters the large intestine via the cecum.

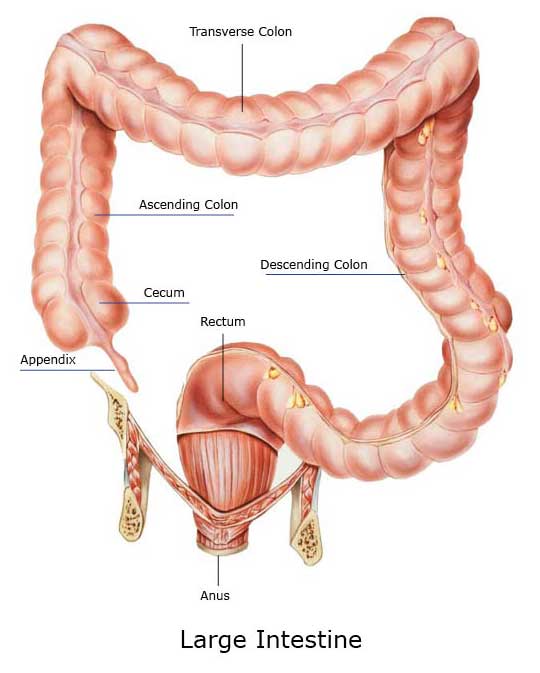

Large Intestine

The large intestine forms the last part of the digestive tract, and is about 5 feet long, and wider in diameter than the small intestine. Because it lacks villi and microvilli, it has less surface area. The large intestine can be divided into the cecum, colon and rectum. The colon is further subdivided into the ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid regions.

Undigested food waste passes from the small intestine into the cecum, the colon’s entry point. Upon entering the ascending colon, absorption of water, salts, and other electrolytes begins. This fluid travels up the ascending colon, across the transverse colon, and down the descending colon. It then passes into the S-shaped sigmoid colon, and then to the rectum. The colon absorbs up to 50 ounces of water every day.

After absorption, the remaining undigested matter is squeezed into a bundle called feces. Feces consists of fiber, undigested food, cells that slough off from the intestinal lining, and bacteria. About 30% of the weight of feces is bacteria.

Some bacteria are “good,” and billions of them live inside colon to make up the gut microbiome. A healthy gut microbiome is important not only for digestion, but immunity and prevention of chronic diseases. Some of these bacteria produce vitamin K within the intestines, and promote the absorption of vitamin B12. They also break down amino acids to make nitrogen, and ferment fiber to form gas. These bacteria are harmless as long as they don’t spread to the other areas of your body.

The final feces then passes into the rectum where it is stored until it is excreted as a bowel movement. The opening at the end of the rectum, called the anus, has voluntary and involuntary sphincter muscles which can detect the difference between gas and solid contents.

Right where the ileum meets the cecum is an organ remnant, the appendix. This organ had a purpose in prehistoric humans, but is now useless. Although this organ is currently of no use, it is problematic when it becomes inflamed. This is a disorder called appendicitis.

Accessory Digestive Organs and Glands

While they are not directly part of the digestive tract, the accessory digestive organs play a major role in digestion. They include the salivary glands, pancreas, liver and gallbladder. Glands are organs that secrete hormones or chemicals that are important for various body functions.

Salivary Glands

There are three pairs of salivary glands:

- parotid glands (the largest of the salivary glands, one in each cheek, located between the ear and the lower jaw)

- submandibular glands (also called submaxillary glands, on the floor of the mouth)

- sublingual glands (in front of the submandibular glands, under the tongue)

All three secrete saliva, a mixture of water, mucus, and enzymes, needed to moisten and soften food during chewing and ingestion. One particular enzyme, amylase, helps break down starches in food.

Pancreas

This carrot-shaped gland is located behind and under the stomach. It functions both as an endocrine and exocrine gland. The exocrine component secretes the pancreatic enzymes amylase and lipase which pass through the pancreatic duct, and into the duodenum. This duct is also associated with the bile duct. The enzymes further breakdown food carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

As an endocrine gland, the pancreas secretes the hormones insulin and glucagon. Insulin is important for digesting carbohydrates, and regulating the amount of sugar that circulates in the bloodstream. The pancreas also secretes gastrin and amylin to stimulate gastric acid production in the stomach.

Liver

The liver is the body’s chemical-processing center. It is the largest organ of the human body, and sits below the diaphragm in the upper epigastric region of the abdomen. It has many functions, including protein synthesis, production of chemicals necessary for digestion, and removing toxins. For example, many medications are metabolized by the liver which prevents their effects from lasting too long. However, a major function of the liver is bile production. This yellowish-green fluid aids in the digestion and absorption of fats. In addition, the liver releases nutrients and electrolytes from food to cells throughout the body. It also stores glucose, iron, and vitamins A and B12, in addition to processing vitamin D into a usable form.

Gallbladder

The gallbladder is a small organ located just below the liver. It is about 3 inches long, and is shaped like a hollow balloon. Its primary function is to store bile produced by the liver, and release it into the duodenum when fatty foods are present. While it is stored in the gallbladder, bile becomes more concentrated and, therefore, more effective in breaking down fats.

The gallbladder is a small organ located just below the liver. It is about 3 inches long, and is shaped like a hollow balloon. Its primary function is to store bile produced by the liver, and release it into the duodenum when fatty foods are present. While it is stored in the gallbladder, bile becomes more concentrated and, therefore, more effective in breaking down fats.

Digestive System Problems and Diseases

Disorders of the digestive system range from common digestive problems (i.e. infectious diarrhea) to chronic diseases. Some examples include inflammatory bowel diseases, irritable bowel syndrome, lactose intolerance, ulcers, or even cancers of the stomach or colon.

Diarrhea

Watery stools that occur over a short period of time are called diarrhea. It may be caused by an infection or an offending food. This is a very common problem, and most often resolves on its own. It may also occur due to an intestinal/functional disorder which often needs specific treatment by a doctor (gastroenterologist). Not only is water lost in diarrhea, but important electrolytes. Dehydration is a common side effect, and thus fluid losses should be replaced with frequent intake of oral rehydration fluids.

Diverticular Disease

In some people, especially the elderly, the colon begins to form sac like protrusions called diverticula (singular diverticulum). This condition is known as diverticular disease. It is generally caused by constipation, and increased pressure on the colon while passing stool that is too hard. This pressure causes weak parts of the colonic wall to bulge and form diverticula. Diverticulosis is common in people over 40, men, and those who consume diets low in fruits and vegetables. In most cases, it rarely causes symptoms or complications. If the diverticula become infected, a condition called diverticulitis, treatment by a doctor is necessary. The abdominal pains of diverticulitis can be quite severe, and require hospitalization. In rare instances, surgery may be required to correct the problem.

Gastroenteritis

Often called stomach flu, this is a temporary illness caused by a virus, bacteria, or parasite. It affects the stomach and intestines, causing nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Gastroenteritis is typically managed by your regular doctor.

Heartburn

Heartburn or GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease) is a condition in which gastric juices, food, and/or fluid from the stomach flows back into the esophagus, causing pain. The etiology is often multifactorial. Common causes are overeating, or consuming fatty foods, caffeine, sulfates, or peppermint. Heartburn is a common complain during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. It may also be a result of an underlying medical condition such as constipation or a hiatal hernia. The latter is where a portion of the stomach pushes up into the chest through an opening in the diaphragm. Most cases of heartburn are relieved by over-the-counter antacids or diet and lifestyle modifications as recommended by your doctor. However, heartburn may mimic more serious conditions like heart disease. If the chest pains are associated with sweating, light-headedness, and nausea, emergency services should be contacted.

Gas in the Digestive Tract

Gas forms in the digestive tract either as a result of swallowing air, or from the breakdown of foods by colonic bacteria. This collection of gas can cause bloating, pain, and discomfort in the abdomen. Gas is released by burping or as flatulence. Some situations, however, may need medicines or a dietary change to release or prevent gas. Aerophagia, or air swallowing, can be reduced by eliminating its causes such eating or drinking too fast, gum chewing, smoking, and poorly fitted dentures.

Hepatitis

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver. Although it may develop as a result of alcohol consumption or certain medications, most cases are due to viral infections. The virus responsible for infectious mononucleosis can cause such inflammation, but more serious cases result from the group of hepatitis viruses. There are six types: hepatitis A, B, C, D, E, and G. Hepatitis A and E are acquired by eating food or drinking water that is contaminated with feces. Hepatitis B, C, and D are spread from by contact with and infected person’s body fluids such as saliva, blood, semen, or vaginal secretions. It can also be transmitted to a baby born to an infected mother. These types of hepatitis are more severe, and can cause chronic liver damage or death. Effective vaccinations are available for hepatitis A and hepatitis B. The latest form of hepatitis is hepatitis G. Though very little is known about it, hepatitis G is also believed to be spread via body fluids or maternal transmission. Most cases are asymptomatic.

Gallstones

Gallstones are a common disorder of the gallbladder. They form when there is too much cholesterol in bile. In cases of chronic inflammation and pain, removing the gallbladder may be necessary. Gallstones can grow as large as the size of a golf ball.

Inflammatory bowel diseases

Ulcerative colitis

In this type of inflammatory bowel disease, the inner lining of the colon and the rectum become inflamed. It is a chronic disease with an unknown cause. It generally does not affect the small intestine, but the ileum may be involved in some cases due to its proximity to the colon. Common symptoms include diarrhea, blood in stools, abdominal cramping, and weight loss. At the time of diagnosis, hospitalization may be required to manage the loss of blood, fluid, and electrolytes. Symptoms are then controlled with dietary modifications and medication to reduce the inflammation. In very few cases, a patient might need to have surgery to remove the affected colon, especially if there is risk of excessive bleeding, bowel perforation, or cancer.

Crohn’s Disease

The cause of Crohn’s disease is also unknown. Although it primarily affects the deeper layers of the terminal ileum, it may develop anywhere in the digestive tract. There is no cure for Crohn’s disease, but medications are prescribed to reduce the inflammation. Dietary modifications can also help, and supplements may correct nutritional deficiencies. In treatment resistant cases, the troublesome portion of bowel is surgically removed. Surgeons may place a temporary ileostomy or colostomy until the inflammation improves enough to reconnect healthy portions of the intestines. There is also a risk that surgery might affect the area adjacent to the removed section of the bowel.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

This is a functional disorder, primarily of the colon. It is associated with intermittent abdominal pain, bloating, and changes in bowel habits. The exact cause of this disorder is unknown, but is believed to be associated with emotional stress and/or an improper diet. Doctors usually treat this disorder with diet modification, probiotics, and medicines such as antidepressants, laxatives, antidiarrheals, or bowel motility agents. Fiber supplements may also be recommended. However, some patients become dependent on laxatives or antidiarrheals which can have side effects.

Lactose intolerance

Lactase is an enzyme produced in the small intestine. It breaks down the lactose found in milk products into a form that can be easily absorbed. When there is insufficient lactase, the body can’t digest this sugar. This is called lactose intolerance. Most cases occur due to a genetic predisposition, and it is more common among certain ethnic groups. Temporary lactose intolerance can develop following an episode of infectious diarrhea, and it may be associated with inflammatory bowel disorders. There is no treatment to improve the body’s ability to produce lactase, but a lactase supplement may be recommended. Lactose intolerance is primarily controlled by avoiding foods that contain this sugar.

Peptic Ulcers

An open sore or lesion on the skin or a mucous membrane is called an ulcer. A peptic ulcer is specifically one that develops on the lining of the stomach, although other types may be found in the duodenum of the small intestine. In the past, stress and diet were thought to be the cause of this disease. Research has shown, however, that the primary cause is a bacterial infection known as Helicobacter pylori. Alcohol consumption, and medications such as NSAIDs and steroids are other possible triggers. Peptic ulcers are quite painful, and can result in bleeding, perforation, or stomach narrowing and obstruction. If caused by Helicobacter pylori, a regimen of antibiotics, acid blockers, and a coating agent are typically prescribed. Lifestyle changes may also be recommended. Patients who fail to respond these interventions, or develop complications may need surgery (i.e. vagotomy, antrectomy or pyloroplasty) performed at the site of the ulcer.

Cancers

Like any other part of the body, cancer can form in the digestive tract. Stomach and colorectal cancers are the most common types. The exact causes these cancers are unknown, but it is believed that cells become cancerous due to certain risk factors. These include dietary habits, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, H. pylori infection, age, ulcerative colitis, and hereditary predisposition. Surgery to remove the cancerous tissues (i.e. gastrectomy or segmental resection of the colon), radiation therapy, or chemotherapy are possible treatment options. Cancers are treated by an oncologist.