The knee joint is a synovial joint which connects the femur (thigh bone), the longest bone in the body, to the tibia (shin bone). There are two main joints in the knee: 1) the tibiofemoral joint where the tibia meet the femur 2) the patellofemoral joint where the kneecap (or patella) meets the femur. These two joints work together to form a modified hinge joint that allows the knee to bend and straighten but also to rotate slightly from side to side.

The knee joint is the largest joint in our body. It is vulnerable to injury as it bears an enormous amount of pressure while providing flexible movement. When we walk, the load on our knees is equal to 1.5 times our body weight. When climbing stairs it is equal to 3-4 times our body weight. When we squat, the load on our knees increases to about 8 times our body weight!

Anatomical Terms

Anatomical terms allow us to describe the body and body motions more precisely. Instead of a doctor simply saying that “the patient’s knee hurts”, he or she can say that “the patient’s knee hurts anterolaterally” to specify where exactly in the knee you are having pain. Identifying specific areas of pain helps to guide the next steps in treatment or work-up. Below are some anatomic terms doctors use to describe location (as applied to the knee):

- Anterior — if facing the knee, this is the front of the knee

- Posterior — if facing the knee, this is the back of the knee. If used to describe the patella (knee cap), then it would refer to the side of the patella closest to the femur.

- Medial — the side of the knee that is closest to the other knee, if you put your knees together, the medial sides of each knee would touch

- Lateral — the side of the knee that is farthest from the other knee (opposite of the medial side)

- Abduction — move away from the body (raising the leg away from midline i.e. towards the side)

- Adduction — move toward the body (lowering the leg toward midline i.e. from the side)

- Proximal — located nearest to the point of attachment or reference, or center of the body

- example: the knee is proximal to the ankle

- Distal — located farthest from the point of attachment or reference, or center of the body

- example: the ankle is distal to the knee

- Inferior — located beneath, under or below

- Superior – located above

Structures often have their anatomical reference as part of their name, particularly if there are other similar structures close by. For instance, there are two menisci (or meniscus, singular) in the knee. As such, they are named the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus. Therefore, the medial meniscus would refer to the meniscus on the inside of the knee (i.e. closest to the other knee).

Structures of the Knee

Again, the knee joint is a hinge type joint. The part of the door that keeps it secured to the wall and allows it to open and close is called a hinge. The majority of the movement allowed by the knee is the same type of motion allowed by a door hinge. It additionally allows for a small amount of rotational movement.

If you think of the knee in layers, the deepest layer is bone and ligaments, then ligaments of the joint capsule, then muscles on top. Various nerves and blood vessels supply the muscles and bones of the knee.

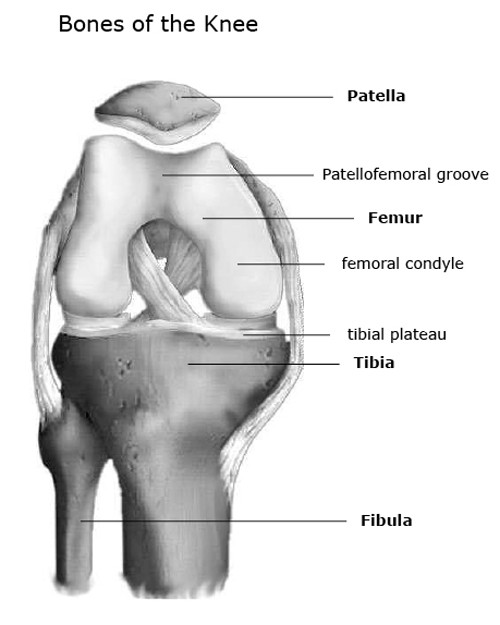

Bones of the Knee

There are four bones around the knee: the thigh bone (femur), the shin bone (tibia), knee cap (patella), and the fibula (see image to the left):

- Femur (thigh bone) – the longest bone in the body; The round knobs at the end of the bone (near the knee) are called condyles. Within the knee joint, the end of the femur is covered in hyaline (or articular) cartilage.

- Tibia (shin bone) – runs from the knee to the ankle. The top of the tibia is made up of two plateaus (or flat surfaces) which are covered in articular cartilage (within the knee joint). Attached here are two C-shaped shock-absorbing cartilages called menisci. A knuckle-like protuberance on the front (or anterior aspect) of the knee is called the tibial tubercle. The patellar ligament (or tendon) attaches here (see below).

- Patella (kneecap) – a semi-flat, triangular bone that is able to move as the knee bends. It’s main function is to increase the force generated by the quadriceps muscle (which straightens or extends the knee). For instance, if you break (or fracture) the patella, the quadriceps may not be able to effectively pull on the tibia and you may not be able to straighten your knee. This is one of the main reasons why patellar fractures often need to be fixed. The patella also protects the knee joint from trauma. The patella glides within the groove formed between the two femoral condyles called the patellofemoral groove.

- Fibula— a long, thin bone in the lower leg on the lateral side which runs along side the tibia from the knee to the ankle. While about 80-90% of weight is carried by the tibia, the fibula does help to carry some weight as well. Importantly, it serves as an attachment for muscles like the biceps femoris (one of the hamstring muscles), lateral collateral ligament (see below), and also helps to form the ankle joint.

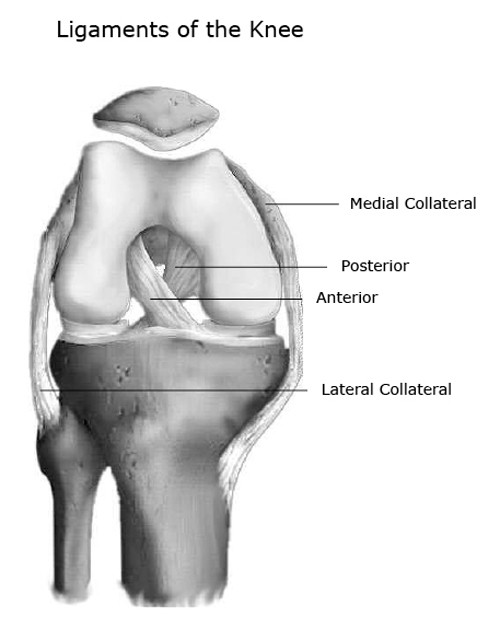

Ligaments in the knee

Ligaments are strong, tough bands that are not particularly flexible. The function of ligaments is to attach bones to bones and to help keep them stable. In the knee, they give stability and strength to the knee joint as the bones and cartilage of the knee have very little stability on their own.

- Medial Collateral Ligament (or the tibial collateral ligament) – attaches the medial side of the femur to the medial side of the tibia and limits sideways motion of your knee.

- Lateral Collateral Ligament (or the fibular collateral ligament) – attaches the lateral side of the femur to the lateral side of the fibula and also limits sideways motion of your knee.

- Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) – attaches the tibia and the femur. It’s located deep inside the knee and in front of the posterior cruciate ligament. It mainly serves to limit forward motion of the tibia relative to the femur. It also limits some rotation and sideways motion of the knee. The ACL can be torn with sudden pivoting motions of the knee.

- Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) – like the ACL, it attaches the tibia and the femur. It lies behind the anterior cruciate ligament. It mainly limits backward motion of the tibia relative to the femur. Like the ACL, it also limits some rotation and sideways motion of the knee. The PCL can be torn with a forceful landing on the shin.

- Patellar ligament (or tendon) – attaches the kneecap to the tibia. It is less of ligament and actually a continuation of the quadriceps tendon.

- Joint Capsule – a thick, fibrous structure that wraps around the knee joint. Inside the capsule is the synovial membrane which is lined by the synovium, a soft tissue structure that secretes synovial fluid, the lubricanr of the knee.

The pair of collateral ligaments keeps the knee from moving too far side-to-side. The cruciate ligaments crisscross each other in the center of the knee. They allow the tibia to “swing” back and forth under the femur without the tibia sliding too far forward or backward under the femur. Working together, the 4 ligaments are the most important in structures in controlling stability of the knee.

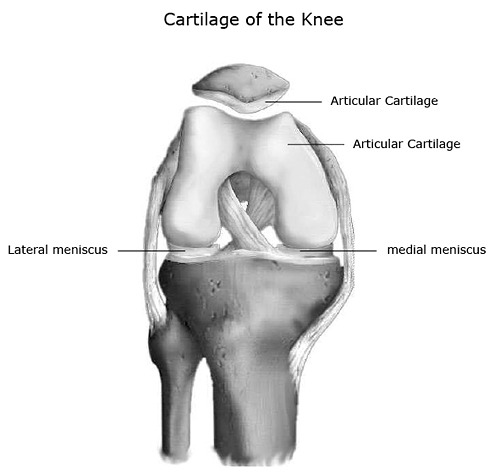

Cartilage of the Knee

There are many types of cartilage in our body, each with a slightly different function. For instance, the medial and lateral meniscus (discussed below) are made up of fibrocartilage which make them strong and rubbery and able to add additional stability to the knee. On the other hand, like bones of most joints, the end of the femur and tibia and the undersurface of the patella are covered in hyaline cartilage. Hyaline (also known as articular) cartilage is both flexible and slippery. The flexibility helps it to act as a shock absorber. Articular cartilage is made even more slippery by an oily lubricant made within the joint, called synovial fluid. This allows the two bones to move smoothly on each other without pain. If this articular cartilage wears away, joint movement can become painful and limited (this is known as arthritis). Unfortunately, cartilage has almost no blood supply and is very bad at repairing itself.

Medial Meniscus

The medial meniscus is a crescent shaped structure that exists on the inside of the knee. It is made of fibrocartilage. It acts as a shock absorber in the knee and adds stability to the knee joint. It is attached to the tibia as well as to the joint capsule of the knee.

Lateral Meniscus

The lateral meniscus sits on the lateral tibial plateau. It is a crescent shaped structure that is also made up of fibrocartilage. It acts as a shock absorber in the knee and adds stability to the knee joint. It is attached to the joint capsule of the knee as well. It is somewhat more mobile than the medial meniscus.

In a healthy knee, the rubbery menisci act as shock absorbers. They both sit on top of the tibia and help to spread the load of the femur over a larger surface area on the tibia. If the menisci are removed (because they are torn, etc.) the underlying articular cartilage sees a heavier load and is at risk of wearing down faster (i.e. development of osteoarthritis)

Additionally, together, the menisci create a shallow socket on the tibia that accommodates the end of the femur. This assists with knee stability.

Muscles Around the Knee

The muscles around the knee help to keep the knee stable, well aligned, and moving. There are two main muscle groups around the knee: the quadriceps and the hamstrings. The quadriceps are a collection of 4 muscles on the front of the thigh and are responsible for straightening the knee by bringing a bent knee to a straightened position. The hamstrings are a group of 3 muscles on the back of the thigh that provide the opposite motion by bending the knee from a straightened position.

The iliotibial band is a broad tendinous extension of the tensor fascia lata and gluteus maximus that also helps to stabilize the knee.

Tendons in the Knee

Tendons are elastic tissues made up of collagen. They are the continuations of muscles and allow them to connect to bones. There are numerous tendons around the knee that also help to stabilize the knee. They are associated with muscles discussed in the section above (see above). One of the most important tendons is the quadriceps tendon. This lies on the front of the knee and connects the quadriceps muscles of the thigh to the tibia via the patella and patellar ligament (or tendon). It provides the power necessary to straighten the knee.

Bursae

There are up to 13 bursa of various sizes in and around the knee. These fluid filled sacs cushion the joint and reduce friction between muscles, bones, tendons and ligaments. There are bursa located underneath the tendons and ligaments on both the lateral and medial sides of the knee. The prepatellar bursa is one of the larger bursae of the knee and is located on the front of the patella (hence pre-patellar) just under the skin. It protects the patella. Sometimes, whether due to direct trauma or even infection, it can become irritated, swollen, and painful. This is known as prepatellar bursitis.

The pes bursa is another important bursa that overlies some of the hamstring tendons which attach to the medial side of the tibia. It too can sometimes become irritated, causing pes bursitis, which can be painful.

Plicae

Plicae are folds in the synovium within the knee joint itself. Plicae rarely cause problems but sometimes can get caught between the femur and patella and cause pain.

Knee Arteries and Veins

Probably the most important thing to know about the blood supply to the knee is that it is very abundant. There are many collateral vessels (basically extra vessels) that give blood supply to the structures of the knee.

Problems in the Knee

As the knee has many structures associated with it, there are many problems that can occur around the knee. In addition to wear and tear type issues of the knee, sports injuries are the source of many knee problems.

Symptoms

Knee symptoms can be quite variable. Pain can be dull, sharp, constant or an on-and-off type pain. As there are many structures of the knee that are prone to injury, depending on the underlying problem, the location of pain can be variable as well.

With certain types of injuries (ligamentous injuries), knee range of motion may actually increase as the knee becomes unstable. On the other hand, with arthritis of the knee, range of motion can decrease.

Depending on the injury, you may experience “mechanical symptoms”. Mechanical symptoms are ones that affect the normal function of the knee. Catching or locking of the knee, whether painful or painless, are examples of mechanical symptoms (see below). Additionally, you may hear grinding or popping (crepitus).

- Swelling

- One of the most common symptoms associated with knee problems is local swelling. The accumulation of too much synovial fluid (synovial effusion) is usually due to irritation or inflammation of structures within the joint. Bleeding into the joint (called a hemarthrosis) can also cause a joint to swell. Swelling immediately following an injury is usually from bleeding. More delayed swelling or on-and-off swelling are usually from excess synovial fluid production from an irritated knee. The best initial home therapy for swelling is R.I.C.E. therapy.

- Chronic swelling can start to limit full range of motion. This may eventually lead to muscle atrophy (or wasting) from non-use of the muscles around the knee.

Locking (or Catching)

Locking or catching of the knee usually occurs when there is a loose body or a torn meniscus in the knee. The loose body can be as small as a grain of sand or as big as a quarter. It is usually a piece of cartilage that has been chipped off of the end of the femur or tibia or a piece of torn meniscus that has become free. As it floats around the knee, it can suddenly limit normal motion and be associated with significant pain. A torn flap of meniscus (that is still attached) can do the same thing. If the symptoms are bad enough, knee arthroscopy may be needed to address the issue.

Giving Way

Sometimes, depending on the underlying problem, your knee may occasionally feel unstable and you may feel like you’ve momentarily lost control of the muscles around the knee. This may cause you to stumble or even fall. There are many reasons why this can occur, including injuries to ligaments. Sudden sharp pains in the knee from a loose body or a torn meniscus can also cause your knee to reflexively feel weak and give way.

Snaps, Crackles and Pops

Popping or crackling noises – medically termed crepitus – coming from the knee without any associated pain are oftentimes normal. However, If you have pain, swelling or loss of knee function, you should seek the opinion of an orthopedic surgeon. The most common causes of crepitus are osteoarthritis and a condition called —chondromalacia patella—where the cartilage under the patella starts to wear down. These conditions result in rough surfaces within the knee that rub on each other and cause noise (i.e. crepitus).

If your symptoms are interfering with your quality of life, you should see an orthopedic surgeon to have your knee evaluated. He or she will perform a history (ask you questions about your symptoms and how they started) and a physical exam. Imaging studies then may be ordered to help figure out what is causing your symptoms. If you have had imaging studies performed elsewhere, it is always best to bring the actual CD of the study (i.e. not just the report) to your surgeon so that they can actually look at it in person. This will speed up the time it takes to figure out how to best treat your problem.

Pathological Conditions and Syndromes in the Knee

- Osteoarthritis

- Osteochondritis Dissecans

- Infectious Arthritis

- Chondromalacia Patellae

- Gout

- Plica Syndrome

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) Injury or Tear

- Meniscus tear

- Lateral and Medial Collateral Ligament Injury

- Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) Injury or Tear

- Patellar Dislocation and Instability

- Patellofemoral syndrome (Runner’s Knee)

- Patellar Tendon Rupture

- Iliotibial Band syndrome

- Pes Bursitis

- Fracture and Stress Fracture

- Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Types of Knee Surgery

Note that the information in this article is purely informative and should never be used in place of the advice of professionals.