As you get close to your due date, you’ll start thinking about labor and giving birth. It’s normal to start looking for signs that labor is near or has started. There are several signs you can watch for. These signs may or may not happen and when they do, they can happen in any order and over weeks or hours.

Some women have very distinct signs. Their first “labor” contraction feels different that any other contraction they felt during pregnancy. Also, the contractions continue at predictable intervals. For other women, it’s hard to identify labor contractions when they start and stop over a period of time. Uterine contractions aren’t the only sign your labor is about to begin. There are other changes that can happen before contractions start.

NOTE: It’s important to learn about preventing preterm birth and call your doctor right away if you are having signs of labor before 37 weeks.

Lightening

If this is your first birth, the presenting part of your baby may move down into your pelvis about 2-3 weeks before the first stage of labor begins. Lightening is the baby’s descent down into the pelvis. If this is not your first birth, lightening may not happen until you’re in labor. Before your baby moves down into the pelvis, you may feel like you can’t get a deep breath because your baby pushes up your diaphragm and lungs. You may have felt pressure on your stomach.

Your baby moving further down into your pelvis takes pressure off your lungs, giving you more room to breathe. If you’ve had heartburn, you’ll probably get some relief as pressure on your stomach is also reduced. However, when your baby moves further down, the uterus and baby press on your bladder. The added pressure on your bladder makes you feel like you have to pee more often.

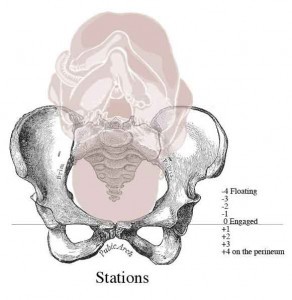

Baby Stations

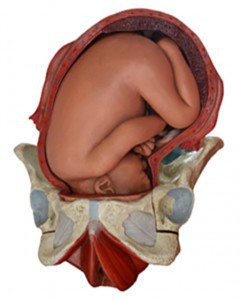

The location of your baby’s leading part—usually the head—within your pelvis is judged in relation to two bony projections in the middle of your pelvis called ischial spines. This level of the pelvis is called ”zero station.” On vaginal examination, when the leading part reaches zero station it is ”engaged” in the pelvis. The location of the leading part is estimated in centimeters above and below zero station and described as ”station plus 1” or ”station minus 2,” etc. Locations above zero station are -1, -2, -3, etc., and mean your baby’s head is above the spines or floating. Locations at +1, +2, +3, etc mean your baby is below zero station. Numbers +3 to +5 mean your baby is crowing and it’s time for delivery. Zero station is at the ischial spines of the pelvis. During labor, your baby’s movement (descent) through your pelvis is an important sign of how your labor is progressing. (In our illustration, the leading part is the baby’s head, and is shown at zero station. Each increment is 1 cm.) Ideally, you should not push until your baby is engaged even if you are fully dilated.

Several major nerves and blood vessels run through your pelvis and branch down into your legs. When your baby’s head is down in your pelvis there is pressure on these nerves and blood vessels that may cause leg cramps and swelling in your feet and ankles. It’s important to reduce swelling and pain of your feet and legs by getting off your feet several times a day. Prop up your feet and legs when you can.

Rupture of the Amniotic Sac

In about 12 percent of women, the amniotic sac, or “bag of waters,” breaks on its own before labor begins. In most women, the sac does not break on its own until late in labor. When your due date gets near, protect your furniture and bedding from amniotic fluid by covering them with a plastic sheet or a layer of towels if your amniotic sac ruptures.

The sac may break near the opening of the uterus and you’ll have a gush of amniotic fluid. Although it may seem like a lot of fluid comes out, there’s still more fluid behind the baby’s shoulders, which will leak out each time you have a contraction.

The sac can also break higher up in the uterus and you’ll have a “slow leak” of fluid. Since many pregnant women leak a bit of urine with pressure on their bladder when they sneeze or cough, you may not realize it’s the amniotic fluid that’s leaking. You can tell the difference because urine is usually yellow and amniotic fluid is usually clear and smells like weak bleach.

In about 80 percent of women, near the end of pregnancy, labor will begin on its own within 24 hours of the amniotic sac breaking. When your “bag of waters” breaks write down the time, how much fluid came out, did the fluid leak or gush out, and the general color and smell of the fluid. Call your doctor’s office and give them this information. Some doctors may want to induce labor while other doctors are content to wait and see if labor starts on its own.

Once your sac ruptures, don’t try to control the leaking fluid by putting a tampon in your vagina or try to check yourself with your finger. This will reduce the chance of infection. Use menstrual pads to soak up the fluid, and change the pads often to keep the area dry. Don’t have intimate relations. Take showers instead of tub baths.

Sudden Burst of Energy

Some women notice a sudden burst of energy about 24 to 48 hours before labor begins. After feeling tired for the last few weeks, you may find that you suddenly want to rearrange your home or clean everything in sight. If you find yourself cleaning and moving furniture—stop. You can pack your suitcase for the hospital, then rest and save your energy for labor and birth.

Weight Loss

You may notice that you’ve lost 1-3 pounds. This can result from your hormone levels changing just before labor begins.

Other Signs

Some women have indigestion, diarrhea, or nausea and vomiting right before labor begins. The cause for the flu-like symptoms are unknown but may be your body’s way of getting ready for the birthing process.

Still other women say they just felt “different” the day they went into labor. They may have felt like they didn’t want to do their normal daily routine.

Onset of Labor

The actual onset of labor is often uncertain. But there are two main ways that true labor is recognized.

- Progressive opening and thinning of the cervix

- Palpable uterine contractions; palpable contractions are ones you can feel with your hands.

Labor is divided into 3 stages. the first stage—the progressive dilation and effacement of the cervix—is completed with the cervix has fully dilated, usually 10 cm. The first stage of labor is further divided into the latent phase and the active phase. The first stage averages 12 hours for first-time mothers and 8 hours for later births. The active phase is regular contractions (every 2-5 minutes, lasting 45-90 seconds) that result in increasing cervical dilation and descent of the baby’s presenting part. Active labor lasts about 1-4 hours. During active labor is usually when the bag of waters breaks.

Changes in the Cervix

The cervix is a firm muscle that makes a strong base at the bottom of the uterus.Throughout pregnancy the cervix—the opening to the uterus—forms a protective barrier and stays long, firm, and closed. In late pregnancy, hormones cause the cervix to soften and thin out allowing your baby to be born.

- The Cervix

- The cervix is located at the bottom of the uterus. When you’re not pregnant, your cervix is long, narrow, and thick. It has a tiny opening that allows menstrual blood to flow out of the uterus. When you become pregnant, a mucous plug forms inside the long neck of the cervix to protect your baby from infection. This plug doesn’t let anything into or out of the uterus.As labor approaches, the cervix loses its firmness and starts to soften in response to enzymes in the blood. Once the cervix softens, it will shorten. When the uterus begins contracting, it pulls on the cervix and causes it to change shape. It changes its shape by becoming shorter and thinner, called effacement. Effacement is measured in percentages from 0% to 100%. At 100% the cervix is as thin as paper. Effacement must occur before dilation can begin.Contractions also cause the cervix to open or dilate. Dilation is measured in centimeters from 0 cm to 10 cm. Ten centimeters are enough for your baby’s head to get through.Changes in the cervix also help decide when you are “officially” in labor. Active labor is established at 3-4 cm. Full dilation is at 10 cm. You cannot push your baby’s head out until you are fully dilated.

Bloody Show

During pregnancy a mucous plug seals the opening of the cervix. This plug may come out of the cervical canal, sometimes as a “blob” but more often as streaks of blood-tinged mucus. The blood is from tiny blood vessels that tear as the membranes separate and the blood mixes with the mucus.

You may notice this “bloody show” over a several hours or even days. It is a sign that your newborn is almost here. If you had a vaginal exam within the last day, you may notice a trace of bright red blood, which is not bloody show; show is also different from the fresh flow of blood for which you should normally call your doctor right away.

Ripening of the Cervix

The cervix must soften so your baby can pass from the uterus into the birth canal (vagina). The softening usually starts in late pregnancy and is a sign of readiness for labor and not a sign of labor starting.

Effacement of the Cervix

Before your cervix can stretch around your baby’s head, it must get shorter and thin out. By the time the cervix has fully opened it will be almost paper-thin. The process of shortening and thinning, called effacement, is measured in percentages from 0 to 100 percent.

Dilation of the Cervix

A vaginal exam is done to check for progressive changes in your cervix. The actual stretching and opening of your cervix around your baby’s head is called dilatation. It is gauged by vaginal exam and the diameter of the opening is measured in centimeters from 1 to 10 cm.

- 1 finger is 2 cm

- 2 fingers is 1/3 dilated

- 3 fingers is 1/2 dilated

- 4 fingers is 3/4 dilated

The cervix can thin out and dilate some during late pregnancy, or it may not change any until true, active labor starts. During true labor, effacement (thinning) and dilatation (opening) usually happen at the same time. It takes a lot of thinning and shortening of the cervix before it can open completely. At 2 cm dilation, the cervix has shortened and is beginning to open; your contractions may still be irregular. At 6 cm dilation, you are in active labor. Your contractions will be more frequent, regular and stronger. At 10 cm you are fully dilated; contractions may be almost continuous and you’re ready to start pushing your baby out.

Uterine Contractions

The uterus is the largest muscle in the human body, male or female. When the pituitary gland releases the hormone oxytocin, it causes the uterus to tighten or contract. The upper part of your uterus, the fundus, tightens and thickens while the lower part of your uterus and cervix relax and stretch. The contractions eventually push your baby through the birth canal and out the vagina. What triggers the release of oxytocin is unknown. Otherwise, it would be far easier to predict the actual onset of labor contractions.

- Labor and Contractions

- Uterine contractions supply the power that makes birth possible. Contractions are strongest in the upper part of the uterus and push your baby down toward the birth canal. Contractions last between 15 seconds at the beginning of labor to 90 seconds toward the end.In early labor, contractions are 15 to 30 minutes apart. Toward the end, they are only two to three minutes apart. The first contractions are usually mild and often painless. As labor progresses they get stronger and more painful. Between contractions there is no pain at all.Uterine contractions press on the amniotic fluid and cause the bag of waters to break. As your baby’s head presses on the cervix, hormones are released that cause the contractions to become stronger and closer together. Effacement and dilation of the cervix are the direct result of effective contractions of the uterus. The cervix thins out and opens so your baby’s head can be pushed through the cervix and delivered from your vagina.

What does a contraction feel like?

Contractions usually begin at the top of the uterus (below your breast) and feel like a tightening or hardening of a muscle. Your uterus will feel harder as the tightness increases to a peak hardness. Then the uterus relaxes or softens as the contraction ends. If you feel your abdomen tighten (contract) and get hard and then soften (relax), you’re having a contraction. You may be able to see your abdomen move as it tightens—when the uterus becomes firm it alters the contour of the abdomen because it rises and moves in the direction of the birth canal as it contracts. This movement is easier if you’re upright and walking may make labor easier. The discomfort with contractions is usually felt in the lower back and lower abdomen.

When the uterus contracts, it will feel firm to your fingertips—like your biceps feel when you “make a muscle.” During a contraction, your whole uterus should feel firm. So spread out your fingers so you can feel a large area of your belly. If you feel a hard “spot,” it may be your baby’s buttocks or a foot—not a contraction. Usually, your baby’s head is down near the birth canal and her bottom and feet are opposite.

Monitoring Contractions

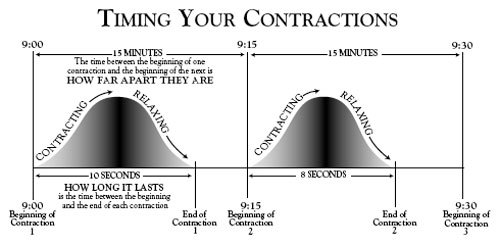

Click on the image to the left to download our contractions worksheet to record your contractions. Self-monitoring contractions means feeling your abdomen to see if you are having uterine contractions and then timing the contractions if you do. Your doctor will tell you how often to watch your contractions. Monitoring contractions includes measuring how long they last, how far apart they are, and how many you have in an hour. Do not trust your memory or guess. If you get upset during the process, you may not be able to remember. So, have pen and paper nearby and a clock or watch with a second hand.

Timing Contractions

Count how many seconds each contraction lasts. When it’s over, write down the time and how many seconds the contraction lasted. If you have more than four contractions in one hour, empty your bladder again, drink at least two 8-ounce glasses of water, and monitor for a second hour. If the contractions start coming closer together or become painful, call your doctor.

How long do contractions last?

The length of a contraction is usually measured in seconds. Begin counting the seconds when the contraction begins (the uterus starts getting hard) and stop counting when the contraction stops (the uterus is soft and has completely relaxed). If you don’t have a watch with a second hand, count “one-thousand-one, one-thousand-two, one-thousand-three”. If you count to one-thousand-ten, and the contraction stops, the contraction lasted about ten seconds.

How far apart are contractions?

The time between contractions is measured in minutes. The time between the beginning of one contraction to the beginning of the next is “how far apart” your contractions are. For example, if your first contraction begins at 9:00 and the next begins at 9:15, your contractions are 15 minutes apart. If a contraction began at 9:00, 9:15, 9:30, 9:45, and 10:00, you had four contractions in one hour. The contractions are “regular” because they happened every 15 minutes.

True Labor Contractions

• Usually irregular and short

• Don’t get stronger or closer together

• Longer intervals between contractions

• Discomfort in lower abdomen and groin

• Lying down may make them go away

• Walking does not make them stronger

• Contractions decrease with sleep.

• Bloody show is usually not present.

• Cervix does not dilate (thin and open)

• Regular contractions, although may be irregular at first

• Get stronger and closer together

• Shorter intervals between contractions;

• Discomfort starts in the back and moves around to the abdomen

• Lying down does not make them go away

• Walking increases contractions

• Contractions continue, even while sleeping.

• Bloody show is usually present.

• Cervix dilates (thins and opens)

False Labor

False labor can be very frustrating when you’re ready but your body is not. Braxton-Hicks contractions, which you may have had before may now be noticeable and you can time them, the sometimes last for hours. You might have contractions for 2 hours on Sunday, 6 hours on Monday, and 3 hours on Tuesday. They may be so strong they keep you up at night; then they are gone by the next morning.

False Labor Contractions

- Usually irregular and short

- Don’t get stronger or closer together

- Longer intervals between contractions

- Discomfort in lower abdomen and groin

- Lying down may make them go away

- Walking does not make them stronger

- Contractions decrease with sleep.

- Bloody show is usually not present.

- Cervix does not dilate (thin and open)

- There is no effacement in the cervix

While these contractions are not real painful and you can cope with them, they can still drain your energy and leave you tired and exhausted by the time your true labor pains begin. If you’re having false labor for several days, it is important to take naps and rest when you can; put your feet up. Take a warm shower and drink something warm, without caffeine. Ask someone to rub your back or feet, get in bed and stay there. You need plenty of rest to be ready for the work of labor.

If you keep having false labor, how can you tell when true labor begins? Over a period of hours, true labor produces measurable progress as your cervix thins out and begins to open. You may have to go to the hospital or birth center to have a vaginal exam to see if your cervix is changing and getting ready for childbirth.

If no changes are taking place in your cervix and you’re sent home after being mentally ready for labor, you may feel very discouraged, embarrassed, and even afraid that something is wrong. Your body is just easing into labor and not jumping into it. If you have had a baby before, you may think that you should be able to know when you’re having true labor. It is not always easy, even for health care workers who see women in labor all the time.

When To Call Your Doctor

Since there is so many ways labor can start, how will you know when to call your doctor? Keep notes about what is happening in early labor along with your doctor’s specific instructions and phone numbers. The instructions will vary according to your pregnancy; how far you live from the hospital or birth center; whether this is your first pregnancy or if you have a history of rapid labor; whether you have had any signs of labor in the last weeks etc.

If you’re not sure what the signs you’re having mean or you feel confused, don’t hesitate to call your doctor and talk about what is happening and what you should do. Call your doctor immediately if you have warning signs such as severe or persistent headache, dizziness or light-headedness, blurred vision, fever, or other unusual sign.

What your doctor will want to know

When you call your doctor, he will want to know as much as he can about your current condition and pregnancy. He may ask many questions, especially if it’s after office hours and your medical records are not available. Be sure to have your pharmacy phone number and be able to answer the following questions.

- Are you having contractions? How far apart are they? How long do they last? How long have you timed them? Are they mild or strong? Are they regular? Do they hurt?

- How long will it take you to get to the doctor’s office? The hospital?

- How many babies are you expecting?

- How many weeks pregnant are you?

- Has the bag of waters broken? (a gush of water or leaking)

- Are you having any bleeding? If so, how many pads have you used?

- Are you having diarrhea, vomiting, chills, or pain?

- Have you ever had a cesarean birth?

Depending on several factors—such as how long it will take you to get to the doctor’s office or the hospital and how many weeks pregnant you are—your doctor may have you monitor your contractions for a while longer, come into the office, or meet him at the hospital.

No Signs of Labor Yet?

As your due date gets close and you haven’t had a single sign that labor is near, you may start feeling frustrated and even have doubts about the birth process. You may think you’ll be pregnant forever. Have faith. Some women go into true labor without any signs of lightening, “bloody show,” cervical effacement or dilatation. Your due date may still be a few days off; spend your time resting and having special time with your partner.

Going Past Your Due Date

Due dates are just a target; the time of actual conception is hard to pinpoint; don’t depend on your baby arriving on your due date. This may be hard to do since you’ve been looking forward to that day for so long. A day that means we won’t always have a backache, that we will get to see our toes again along with that special little face of the baby we are carrying inside. Without meaning to, we get so focused on that date that we invest a lot of our emotions in it. If our due date comes and goes without a baby, our spirits can take a beating—especially since your hormones are changing. Try to stay calm and as upbeat as you can and keep in mind you’re another day closer to your baby arriving.

For most women, labor begins by week 40. However, doctors may wait until the 42nd week (2 weeks after the estimated due date) to declare the mother overdue and recommends induced labor.

While you’re waiting, here are some things you can do. Pack your pregnancy suitcase to take to the hospital. You can also learn about what can happen during birth, such as a cesarean, episiotomy, epidural anesthesia, how to care for your self after your baby is born and go through your layette and see if you have enough diapers, sleepers, etc. Caring for Your Newborn.