An appendectomy is the surgical removal of the vermiform appendix. This is the “gold standard” of treatment for acute appendicitis. “Acute” means that the symptoms and inflammation begin suddenly. Appendicitis usually develops without warning over a period of six to 12 hours. An appendectomy is performed to prevent the rupture of an inflamed appendix, and can be a life-saving procedure. When an appendix bursts, there is an overwhelming risk of infection and complications. Most appendectomies are done laparoscopically. In unique situations, however, adults may be prescribed antibiotics until the appendix can be removed at a later time. Before going further, let’s first understand what are the vermiform appendix and appendicitis.

The Appendix

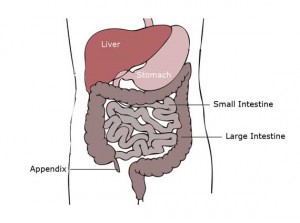

The appendix, located in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, is a three to six inch long, “worm-shaped” structure. Internally, it is lined with a mucus membrane. The distal end of the appendix is closed, and the proximal portion projects from the beginning of the large intestine, or cecum. The function of the large intestine is to re-absorb water back into the body while forming stool. This waste then travels to the rectum, and out through the anus. The appendix is not currently used by the gastrointestinal system, but it was important for digestion in pre-historic humans. It may become blocked by calcium deposits, stool, or bacteria, causing it to produce mucous. As this mucous thickens, the lymphatic tissue swells. The appendix becomes obstructed, swollen, and filled with pus. This condition is called appendicitis.

The appendix, located in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, is a three to six inch long, “worm-shaped” structure. Internally, it is lined with a mucus membrane. The distal end of the appendix is closed, and the proximal portion projects from the beginning of the large intestine, or cecum. The function of the large intestine is to re-absorb water back into the body while forming stool. This waste then travels to the rectum, and out through the anus. The appendix is not currently used by the gastrointestinal system, but it was important for digestion in pre-historic humans. It may become blocked by calcium deposits, stool, or bacteria, causing it to produce mucous. As this mucous thickens, the lymphatic tissue swells. The appendix becomes obstructed, swollen, and filled with pus. This condition is called appendicitis.

It is unclear whether or not appendicitis is hereditary. There are gender and age differences, however. It is more common in girls than boys, but adult men have a slightly higher risk than women. Appendicitis rarely occurs after age 50.

Appendicitis

Symptoms of Appendicitis

The first symptoms of appendicitis are intermittent pain around the umbilicus or right side of the abdomen. It gradually increases to a sharp and persistent pain on the right lower side of the belly. This pain feels worse while moving, taking a deep breath, coughing, sneezing, walking, or riding in a car on a bumpy road. Other symptoms include:

- fever 100.4°F to 104°F (usually develops later)

- nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite

- urinary frequency or pain

- difficulty passing stool or gas

- abdominal swelling (later stages)

- diarrhea (rare)

Blood tests will show an elevated white blood count, possibly with bands on the differential. The presence of bands indicates a bacterial infection. An elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) also reflects inflammation. Appendicitis can be hard to diagnose because many other illnesses have similar symptoms such as a stomach virus, ovarian cyst, or stool impaction. An early diagnosis, however, is important to prevent rupture (when your appendix bursts) and further complications.

If left untreated, appendicitis can be fatal, especially in infants and children. When an infected appendix bursts, the contents of the lower gastrointestinal tract enter the abdominal cavity, and infect the entire peritoneum. When this happens, the pain may suddenly stop. However, the patient may become lethargic, have an abnormally low blood pressure, and look gravely ill.

Acute appendicitis is an emergency. In most cases, it is best to remove the appendix right away. There is no specific prevention for appendicitis.

Complications of Appendicitis

A bowel obstruction may occur due to appendicitis. When the appendix becomes inflamed, it blocks the flow of the intestinal contents, and interferes with the absorptive functions of the intestinal mucosa. This prevents the flow of food, liquids, and gas, causing nausea and vomiting.

An infected appendix can rupture or burst within 24 hours after symptoms begin. This may cause an abscess, a pus-filled boil, to form around the appendix. Alternatively, diffuse peritonitis can develop, a potentially life-threatening infection of the abdominal cavity. Symptoms include mild to moderate abdominal pain, fever, and feeling as if you don’t have enough energy to do your daily activities.

Appendicitis can also spread bacteria into the blood stream, causing a life threatening illness called septic shock. This condition is very serious, and requires treatment in an intensive care unit. In these situations, it is possible for the organs of the body to completely shut down due to the infection.

Diagnosis of Appendicitis

The initial diagnosis of appendicitis is done with a complete history and physical examination. Signs such as an elevated temperature and tenderness when a doctor presses on the right lower part of the abdomen are noted. There is often a sharp increase in pain when the pressure is removed, known as rebound tenderness. Pain may also increase when the doctor flexes the right leg at the hip, and rotates the leg outward. This is called the obturator sign because the inflamed appendix can irritate a portion of the back muscles. To confirm appendicitis, the doctor may order some or all the following tests:

White Blood Count (WBC): The white blood cell count is usually elevated when an infection is present. An elevated WBC count helps confirm appendicitis. However, a WBC alone cannot be used to diagnose appendicitis because it increases with any kind of infection.

Urinalysis: This is the microscopic examination of the urine to determine the presence of red blood cells, white blood cells, or bacteria. An abnormal urinalysis can indicate a bacterial infection, inflammation, or kidney stone. The inflammation may be caused by appendicitis since the appendix is situated very close to the ureter and bladder.

Xray: An x-ray of the abdomen can reveal an intestinal blockage, kidney stone, or constipation. A hard piece of stool may block the proximal end of the appendix, and can be seen on x-ray.

Ultrasound: Ultrasound is a procedure that uses sound waves to examine various organs in the body. Although it may help in the diagnosis of appendicitis, visualization of the appendix is often difficult. Instead, ultrasound may be used to rule out other possible diagnoses with similar symptoms. For example, an ultrasound can show ovarian or fallopian tube problems.

CT Scan: A computerized tomography (CT) scan is the most commonly employed imaging modality for appendicitis. It provides a very clear image of the appendix and surrounding structures. It can also reveal abscesses attached, and other conditions that cause similar symptoms. Because of the high level of radiation it emits, a pregnancy test should be done in anyone of childbearing age.

MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging is a technique that uses a magnetic field to take images of internal body structures. There is no radiation involved. Because of logistical difficulties, MRI is typically reserved to evaluate women who are pregnant.

Treatment of Appendicitis

Instead of surgery, adults who have an uncomplicated case of appendicitis may opt for a 10 day course of antibiotics. This may be an offered when there is no obstruction or enlargement of the appendix, or when surgery would be too risky. However, the likelihood of appendicitis developing again is high, and about 40 percent of these cases require surgery within a year. For this reason, most cases of appendicitis are treated surgically with an appendectomy. This is particularly true for children who have a higher risk of an appendix rupture or sepsis.

Preparing for an Appendectomy

Preparations include the usual pre-surgery tests, such as:

- Blood type

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Blood clotting tests (PT, PTT)

- Urinalysis

- Chest x-ray or EKG if there is an underlying lung or heart condition

The anesthesiologist will want to know how long it’s been since you had something to eat or drink. An empty stomach is preferred when receiving general anesthesia to prevent vomiting during the surgery. If a CT scan helped make the diagnosis, you may have been asked to drink an oral contrast solution to enable better visualization. You may also receive IV to replace fluid losses from vomiting, and antibiotics to prevent sepsis.

Anesthesia

Surgery can be done with either general or spinal anesthesia.

The Appendectomy Procedure

An appendectomy, the removal of the appendix, can be done in two ways: the traditional open abdominal surgery or the more commonly used laparoscopic technique. Open procedures take about an hour, but more time may be required for laparoscopic surgery.

An open appendectomy may be needed for complicated cases. During this procedure, a two to three-inch incision is made through the skin and underlying fat layer of the lower right abdomen. The muscles and organs are separated, and the peritoneum is cut to reveal the cecum. The appendix and any abscesses are identified, then cut away from the colon. Any fluid or pus from the infected appendix is suctioned away. A sample of this fluid may be tested for bacteria. Sometimes, a drain is left in place for a few days. The colon is then repaired with sutures, blood vessels are tied off, and the abdominal cavity is closed. The skin is closed with either sutures or staples which are removed seven to 10 days after surgery.

Most appendectomies are performed laparoscopically. There are no large skin incisions, only a few small puncture wounds. In many cases, one of these incisions is through the umbilicus, so no scar is visible after surgery. The laparoscope, a thin tube with a video camera attached at one end, is inserted through one of these puncture wounds. The doctor is able to view the inside of the abdomen on a TV monitor that is linked to the video camera. The camera allows the surgeon to verify the diagnosis before removing the appendix, and look for other problems. The appendix is removed with instruments inserted through one of the other puncture wounds on the abdomen. Laparoscopy is easier for the patient than an open surgery because there is less postoperative pain, and a shorter recovery time. Most patients are able to go home within 24 hours of having surgery.

If the surgeon is unable to identify the appendix with the laparoscope or unable to remove it due to scar tissue from prior abdominal surgery, an open procedure is necessary. Depending on what is seen laparoscopically, the surgeon may do the open surgery immediately ,or schedule it for a later date.

In some cases, the surgeon may find a normal appendix with no signs of appendicitis. He or she may decide to still remove it to prevent the need to do so in the future.

After surgery, you will be sent to a recovery room for about an hour, then transfer to a hospital room for the remainder of your stay. If your laparoscopic surgery occurred during the evening hours, you will remain in the hospital overnight. If you had an open appendectomy, you may be able to walk around within 6 hours. If there are no complications, you will go home in a day or two. Your doctor will want to make sure you are eating and drinking enough before allowing you to be discharged.

Complications of an Appendectomy

As with any surgery, complications are possible. They may be due to anesthesia, breathing problems, bowel obstruction, side effects of medications, or the surgery itself.

Possible complications from surgery include re-opening, excessive bleeding, or infection of the incision site. Infections can range from mild to severe. Mild infections are associated with slight tenderness or redness around the incision(s). They may be managed with oral antibiotics. Moderate infections require treatment with IV antibiotics, but severe cases may also need surgical intervention. Infections after laparoscopic appendectomies are rare.

An appendectomy that was performed for a ruptured appendix can have other complications that require a longer hospital stay. In very rare cases, appendectomy can have long-term effects such as increasing the risks of Crohn’s disease in young adults.

Recovering From an Appendectomy

After an uncomplicated appendectomy, you may be able to resume normal activities in about two to three weeks. Returning to normal activities can take a little longer after an open appendectomy, if the appendix was ruptured, or there were post-surgical complications. Care during the healing process includes:

Eating and Drinking:

Initially, a liquid diet is recommended to reduce nausea, and to allow your intestines to return to normal functioning. After a few days, you may be able to slowly resume your regular diet. It’s important to eat a balanced diet to speed up the healing process. You may also need a stool softener to avoid straining while your incisions heal, and to relieve constipation caused by pain medicines and the anesthesia.

Incision Care

The incision should be kept clean and dry as recommended by your surgeon. Do not get your incision wet in a tub or shower until your surgeon says it’s OK. If you feel as if you may have a fever, take your temperature. For a fever above 100.4°F for two days, or higher than 102°F, call your surgeon right away. Check your incision daily for signs of infection such as increased redness, swelling, pain, or drainage. Notify your surgeon:

• if you notice any signs of infection, bleeding or discharge at the incision site(s)

• if you have abdominal swelling

• if you have vomiting or diarrhea

After an open surgery, there will be a single, short scar. If your surgery was done laparoscopically, there will be three to four half inch scars where the instruments were inserted into the abdomen.

Returning to Normal Activities:

In most cases, you’ll be allowed to resume regular activities within two to three weeks after surgery. Your surgeon will also give you certain restrictions in order to prevent complications. These can include no heavy lifting or climbing stairs, and not going to the gym, playing sports, running, jogging, or doing any heavy physical activities for six weeks. Avoid driving for two weeks.