The thought of having heart surgery can be pretty scary. You may be most afraid of what you don’t know about it. Like – How should you prepare? What happens during surgery? How long will surgery take? What will recovery be like? How long will it be before you fully recover? Will you ever be the same again? This article will answer many questions for you and hopefully puts some of your fears to rest. But it can’t answer all the questions that you might have about your own heart problem and the treatment of it. Always rely on your doctor and health care team for questions you have about you.

If your heart problem was discovered by your primary care doctor, he probably referred you to a heart specialist or cardiologist. Following an exam and many tests, the cardiologist has recommended surgery to treat your heart problem and referred you to a heart surgeon. This article tells you what to expect during your visit with the heart surgeon. It explains what usually takes place before, during, and after heart surgery. If you have already met with the surgeon, go through the first part of this article to better understand everything you need and want to know before making a final decision about having the surgery. Peace of mind is very important to your good health, a successful surgery and recovery. Your doctors want you to have all the facts so you can make the decision which is best for you.

Your visit with the heart surgeon

Your surgeon will explain the results of your tests and why surgery is being recommended. He will also explain the surgical procedure and the results you can expect. He will tell you about the risks of having or not having the surgery, the benefits of having the surgery and any options you have in place of surgery. You must consider the balance of the risks you will be taking and the benefits you will receive. Don’t be afraid of offending the surgeon or embarrassing yourself by asking questions about anything you don’t understand. The more you know, the more confident you will feel about your decision. To help you get started, here is a list of general questions you can ask. When you ask these questions, be sure you ask how they apply to you, your heart and your overall health.

Questions to ask the heart surgeon

These are general, basic questions to ask your surgeon. If you think of other questions, write them down and bring them with you to your office visit or call your surgeons office and ask. Go over the questions with your spouse and family. Ask if they have questions they would like to have answered. Before you leave the surgeon’s office, try to get all your questions answered—take notes! Be sure you understand everything clearly. If you think of questions after you leave, write them down and call your surgeon back. It’s also a good idea to take someone with you so they can listen and take notes, too.

- How will surgery improve my condition?

- Tell me again what happens during the surgery?

- Will I need blood transfusions? Can I donate my own blood?

- How long will surgery last?

- How long will I be in intensive care (ICU or CCU)?

- How much pain should I expect and how will pain be controlled?

- What will the scar look like?

- What are the possible complications of surgery; how likely are they to happen to me?

- Can I expect to completely recover from surgery? If so, how long will it take?

- How long will I be in the hospital?

- How long will my recovery take once I am at home?

- What will I be able to do and not do during recovery?

- Will I need special equipment when I get home?

- When can I go back to work?

- If I choose not to have surgery, will I get worse or stay the same?

- Is there another treatment that does not involve surgery?

- How long do I have to decide about having surgery?

- If I decide to have the surgery, how soon should I have it?

Making your decision

Once you have the information you need to consider all your options, you may be surprised that the best decision for you becomes pretty clear. That doesn’t mean it’s an easy decision to make, but at least it will be one you will feel good about your decision and will know what to expect as a result of the decision you make.

Types of open-heart surgery

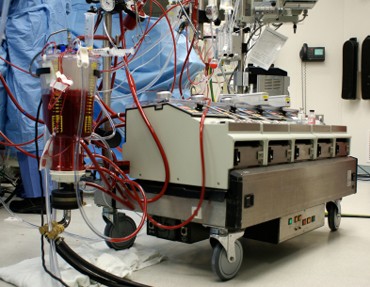

You’re lucky to need heart surgery now and not more than 25 years ago. It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that the heart-lung machine, which takes the place of your heart and lungs and keeps you alive during the operation, could be used safely. This machine, along with improved surgical techniques, medicines, more advanced monitoring machines and more experienced surgeons have made open-heart surgery safer today.

The following are brief explanations of the types of open-heart surgery.

Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)

When your heart muscle doesn’t get the blood and oxygen it needs because one or more or your heart’s arteries are clogged, your surgeon may recommend coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Part of a vein from your leg (saphenous vein) or part of an artery from your chest wall (internal mammary artery) is used to bypass the blocked area in your coronary artery. This new bypass artery improves the flow of blood and oxygen supply. It’s common to have as many as four or five bypass grafts done at one time. Neither your chest wall nor your leg will have permanent harm as a result of the vein or artery being removed.

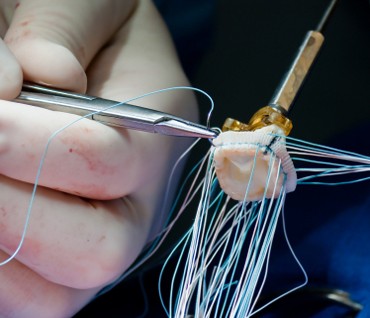

Heart valve repair or replacement (aortic or mitral valve)

Your heart has four valves, one for each chamber of your heart. Each time your heart beats, these valves open and close to let blood in and out of the chambers. One or more of these valves may become damaged from a birth defect, scarring from rheumatic fever or an infection. If medicine can’t correct the problem, your doctor may recommend surgery to repair or replace the valve.

Congenital heart defect repair

A congenital heart defect is a condition that you were born with. About one-quarter of adults who have a congenital heart defect have a condition called atrial-septal defect. This is really a hole in the wall (atria) that separates the two upper chambers in the heart. The hole allows blood with oxygen and blood without oxygen to mix together. Usually, too much blood from the left atrium goes into the right atrium and then into the lungs. During surgery for this condition, the hole is closed and the two chambers are separate as they should be.

Heart muscle disease surgery

There are different kinds of disease of the heart muscle. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a disease of the heart muscle that makes all or part of the heart thicker or overgrown. When your heart muscle gets thicker, it affects blood flow into and out of the heart. Sometimes, surgery can help this condition. If the septum (the wall between the ventricles) is so thick that it sticks out and blocks the flow of blood to the aorta and the rest of your body, the surgeon can remove part of the thickened septum so blood can flow freely to the aorta.

Pericarditis surgery

Pericarditis is when the sac (pericardium) that surrounds the heart becomes inflamed. Although it’s not common, this condition can keep coming back. A surgeon can remove the entire sac from around the heart which usually stops symptoms (like pain and irritation) without causing harm to the heart.

Getting ready for heart surgery

Usually, heart surgery can be scheduled days or weeks ahead of time. It depends on how serious your heart condition is, your schedule and the surgeon’s schedule. If you have a week or two before surgery, use the time wisely. Ask your doctor about:

- Exercise — should you start, stop or continue exercises?

- Diet — should you change your diet in any way?

- Weight — would it help your recovery to lose or gain a few pounds?

- Smoking — if you smoke, STOP! Ask your doctor recommend a stop smoking program? Also ask before using nicotine replacement gums or patches.

- Medicines – what medicines should you start, stop or continue taking? Remember to ask about all medicines that you take regularly or occasionally, including prescription and over-the-counter medicines. Also ask about any food supplements you take that could cause problems with surgery.

Also, be sure to:

- Rest, relax – Take good care of your physical and mental health. Don’t overdo things. And make sure you plan some enjoyable activities to relax your mind and give your spirits a lift.

- Report health changes – Tell your doctor if you have any signs of infection, like chills, fever, coughing, runny nose, or sores within a week of your scheduled surgery. An infection may cause your surgery to be rescheduled to keep you from having complications after surgery.

A special note about smoking

Not only is smoking bad for your health, but it could affect your recovery. Since most hospitals are “smoke free”, you’ll have to quit smoking in the hospital. This means you’ll be going through nicotine withdrawal while your body is also trying to recover from surgery. Do yourself a big favor—quit smoking now, and your mind and body will be able to focus on healing and not withdrawal, too.

Making arrangements for heart surgery

Knowing which foods you’re allergic to can give clues to other things you may be allergic to but haven’t been exposed to yet, like latex.Whether you’re having major or minor surgery, try have a family member or friend with you. Even when you are going for the pre-admission tests (explained later), it’s a good idea to have someone with you. They can listen and take notes for you — or simply hold your hand if that’s what you need! Give your family or friend plenty of notice about upcoming tests and surgery. Make a list of all medicines and food supplements you take and any allergies to medicines, food, etc. that you may have. Take this list with you when you go to the hospital so you don’t forget anything.

Pre-admission procedures

A week or so before surgery you’ll need to have tests. Your surgeon’s office will tell you where to go and which tests you’ll need. If you’ve had any of these tests recently, ask your surgeon if a copy of your test results will do in place of redoing the tests. Test you may need include:

- a chest x-ray to see how well your lungs work

- an electrocardiogram (ECG) and/or an echocardiogram (ECHO) that shows how your heart is working

- blood tests that show chemistry and blood counts

- a urine analysis

There will be paperwork to complete. You will be asked:

- to fill out insurance forms, or give authorization forms from your insurance company; make sure you bring your insurance card(s)

bring a picture ID such as your drivers license - if you brought special orders from your doctor, surgeon or lab test results

- the name, address and telephone number of someone to contact in case of emergency

You will be told about your rights for advanced directives (your options for life support if that’s needed) and asked for a copy of your living will and health care power-of-attorney. You must sign a surgical consent form. This form is a legal paper that says your surgeon has told you about your surgery, alternatives for surgery and any risks you are taking by having the surgery. By signing this form you are saying that you agree to have the surgery and know and accept the risks involved. Ask your doctor about any concerns you have before you sign this form.

Blood transfusion

Surgical methods today reduce much of the blood loss during surgery. However, you may need a blood transfusion. If so, your blood will be carefully matched with blood that has been tested. The blood you receive can come from:

- a blood bank – this blood supply is from the American Red Cross and is safer today than it has ever been

- a designated donor – this can be a family member who has the same type of blood that you do

- you (autologous blood donation) – you will give blood at a local blood bank or hospital

Ask your surgeon which would be best for you. If you give blood, you must do it in plenty of time for surgery. Also, be sure to eat and drink as directed if you decide to give blood.

Being admitted to the hospital

You will usually be admitted to the hospital the day before your surgery. Simply check in at the hospital admissions desk. The hospital should have a record of your pre-admission tests and forms that you completed. If you did not go through pre-admission procedures, you will need to have the tests and complete the forms explained in the Pre-admission procedures section above. Some hospitals will admit you the morning of your surgery.

You will be taken to your room. A nurse will take your temperature, pulse, breathing rate and blood pressure and record it on your chart.

Make sure you tell the nurse about:

- any medicines you are taking (bring a written list with you) allergies you have and allergic reactions

- any other health problems (e.g., eye or hearing problems, dentures)

- how to contact your family

- who to contact in case of emergency

- anything else that will help them care for you

The nurse will let you know if the doctor left any special orders for you to get ready for surgery (e.g., enema or suppository, antibiotic, sleeping pill, etc.). Feel free to ask questions about the hospital, your room and the equipment in it, location of bathrooms, the intensive care unit (ICU) (where you’ll be right after surgery), visiting hours, etc.

Make sure your family asks the nurse about:

- the time of your surgery and how long it might take

- where they should wait for news during and after the surgery

- where the ICU is located and how long they can visit you in ICU

- how and what should they take (e.g., clothes, toiletries, glasses, etc.) to the ICU after your surgery

The night before surgery

Usually, your surgeon and anesthesiologist will visit you the night before or early the morning of your surgery. Your doctor will confirm the time of the operation, review your medical history and do a final physical exam. Now is your chance to ask any last-minute questions or voice any concerns. The anesthesiologist will explain about the anesthesia used during surgery, ask if you have ever had problems with anesthesia during surgery, and how the respirator works.

Sometime that evening, you’ll shower or wash with a special cleansing soap. Your surgical site will be shaved. Shaving rids the body of as many germs as possible and prevents discomfort when bandages are removed. Do not put on any powder or lotion after you wash. And remember, if you feel tired or have pain or discomfort while washing, stop and call a nurse to help you.

Last, but not least, you must stop eating and drinking by mid-night, since anesthesia is safer on an empty stomach.

The day of heart surgery

Before surgery

In the morning before surgery, you can wash your face and hands, brush your teeth, shave and put on your operating room gown. You may not eat or drink anything before surgery. Also, you’ll be asked to remove makeup, jewelry, hair pins, dentures, nail polish, contact lenses or artificial limbs. You’ll probably be given medicine that will make you a little drowsy and relaxed before you’re wheeled to the surgical suite. When you leave your room for surgery, your family or friends will go to the surgical waiting area.

The operation

In the surgical suite, you will be given a local anesthetic so an intravenous (IV) catheter (tube) can be inserted. This IV tube will supply your body with the general anesthesia that puts you to sleep during surgery and medicines. In fact, almost as soon as you begin receiving the anesthesia through this tube you’ll be asleep. There are many electrodes, catheters and tubes that are attached to or inserted in your body. These help watch your body’s functions, remove excess fluid or help you breathe during the surgery.

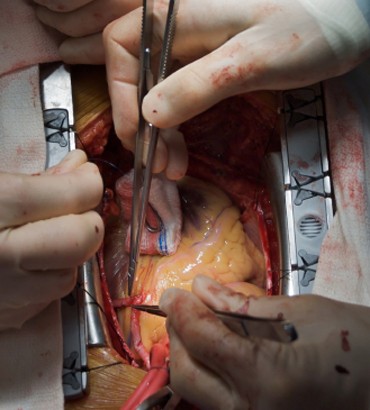

Open-heart surgery requires an incision lengthwise down your breastbone, called the sternum, or crosswise between your ribs. The breastbone is then pried apart. When surgery is done, the breastbone is wired back together and your skin is sewn or stapled together. If you’re having bypass surgery, you may also have an incision in your leg where your leg vein was removed. Your incision(s) may be painful for a few days, then sore for a while afterward. Ask for pain medicine if you need it.

Open-heart surgery requires an incision lengthwise down your breastbone, called the sternum, or crosswise between your ribs. The breastbone is then pried apart. When surgery is done, the breastbone is wired back together and your skin is sewn or stapled together. If you’re having bypass surgery, you may also have an incision in your leg where your leg vein was removed. Your incision(s) may be painful for a few days, then sore for a while afterward. Ask for pain medicine if you need it.

While you’re on the heart-lung machine, the surgeon can repair to your heart while your heart stays still. Usually, when the major part of the surgery is over (when the repair(s) are done, you are removed from the heart-lung machine and your heart begins working again) your family will be told. You will probably stay in the surgical suite for a couple of hours for a total of several hours for the surgery and observation period. Then you’ll be moved to the ICU.

In the intensive care unit (ICU) (Sometimes called CCU – Cardiac Care Unit)

When you’re in ICU, a member of the surgical team will tell your family about the surgery and how you are doing. You’ll be groggy from the anesthesia and unable to speak because of the breathing tube in your throat. You may hear sounds from the equipment around you and hear voices that sound far away. It may be your nurse telling you your surgery is over. You will still have tubes, catheters and monitors attached to or inserted into your body from the surgery. This ICU equipment provides the staff with continuous information on how your body is recovering. You’ll probably be in the ICU for a day or two. Because the nurses are constantly checking on you, this time won’t be very restful. Also, you will have some discomfort and pain. If you need pain medicine, don’t wait too long to ask for it so that you can get the rest you need to heal. The ICU nurses keep a constant watch on your condition and do whatever else is needed to keep you comfortable.

Family visits

Your family can visit you in the ICU for brief periods even though you may drift in and out of sleep at first. They should know you will look pale and your face may be swollen. Because your blood was cooled down for surgery, you will feel very cool and may shiver right after surgery. If your family leaves the hospital, they should let the ICU staff know how they can be reached and when they will be back.

On the road to recovery

Each patient’s recovery rate is different. How quickly you recover depends in part on your physical health before surgery and how complex your heart surgery was. The first step in recovery is breathing deeply and coughing to clear your lungs. When you can do this, your breathing tube will be removed and replaced with an oxygen mask. This could happen as soon as the day after your surgery. Then you may be moved from the ICU to another area of the hospital. Your care will continue as follows:

- you’ll continue to have electrocardiograms to record your heart rhythm

- you’ll wear an oxygen mask as needed

- you’ll continue to have blood tests

- your fluid intake and output will be monitored

- the nurses will help you with turning in bed, coughing and deep breathing exercises

- you’ll start with ice chips and sips of fluid, then solid food

Taking part in your recovery

As you become more active, you’ll bet more involved in your recovery – even while you are still in the hospital. Here are some things you can do:

- eat right – healthy food helps you heal

- keep your lungs free of fluid, which can lead to pneumonia, by practicing your deep breathing and coughing exercises

- get out of bed as soon as you can so your muscles stay strong; start slowly sitting on the side of the bed, then the chair, then short walks, then longer walks

- do the recommended leg exercises to keep your legs muscles strong

- wear elastic or support stockings if your doctor ordered them

- use a chair with a firm back when sitting with pillows on the chair arms; raise your feet to the same height if your legs or feet swell, but don’t cross your legs (this slows blood flow)

Because of your surgery and limited movement right after, fluid can build up in your lungs. This fluid can cause pneumonia and keep you keep you in the hospital longer. Therefore, it is very important that you take deep breaths and cough often. You may be given an incentive spirometer to help you breathe correctly. To ease the pain in your chest when you cough, support your chest incision with a pillow or your hands.

Good days and bad days

After the first few days when you’ve come through the worst of it, your emotions may get the best of you. Don’t be surprised if you have good days and bad days. You may cry more easily, have bad dreams, not be able to concentrate or just feel afraid or down. Some of this is stress, lack of sleep and the effects of the anesthesia and other medicines. It’s not pleasant, but it’s normal after what you’ve been through. Don’t pretend you feel OK when you don’t. Let your family and the hospital staff know. It may help you and your family to talk to a rehabilitation counselor.

Better days ahead

As you near the end of your hospital stay, you’ll be ready to go home. Your mental outlook will improve and your physical recovery may speed up once you’re home. Family, familiar surroundings and peace and quiet can help a lot.

Before you leave the hospital, you’ll be given instructions from your cardiac health care team about a number of things. These include :

- how to care for your incision(s)

- a heart-healthy diet

- a list of physical activities you can do during the next 6-12 weeks

- exercises for you to do

- a list of special equipment, medicines or supplies you’ll need

- the date of your first follow-up visit with the surgeon

Once you’re at home, pace yourself. Follow your doctor’s instructions. Be aware of how you feel during everyday activities. You’ll know when you can increase the level of activity. When you’re tired, rest. When you’re hungry, eat – but eat heart healthy foods!

Congratulations! You’re on your way. Better days are just ahead!

When to call your surgeon

Once you get home you may feel nervous and worried about being on your own. Don’t sit and worry if you think something isn’t right about your health or how you are healing. If you have signs of a heart attack or infection call your cardiologist or surgeon. Keep their phone numbers handy. If the signs tell you it’s a life threatening emergency call 911 right away.

Your stitches or staples will be removed 10 to 14 days after surgery. Check your incision every day. Call you doctor if you see signs of infection.

Warning signs of infection

- red, hot and swollen incisions(s)

- smelly discharge coming from an incision

- a temperature over 100 degrees for a few days

- chest congestion, coughing, and problems with breathing at rest

Warning signs of a heart attack

- intense, steady pressure or burning pain in the center of your chest

- pain that starts in the center of the chest and goes to a shoulder and arm (usually the left) or both shoulders and arms, back, neck and jaw

- prolonged pain in the upper abdomen

- nausea, vomiting, profuse sweating

- shortness of breath, pale skin

- dizziness, feeling light-headed or fainting

- frequent angina attacks like you may have had before surgery

- a sense of anxiety or doom

Warning signs of an emergency

- you are bleeding a lot of bright red blood or you see blood clots

- you have a sharp pain that does not go away with pain medicine

- your incision(s) opens

- if you had leg surgery, your leg turns blue or you lose feeling in your leg

- your fever goes up fast or is over 101 degrees

- you have allergic reactions to medicines you are taking